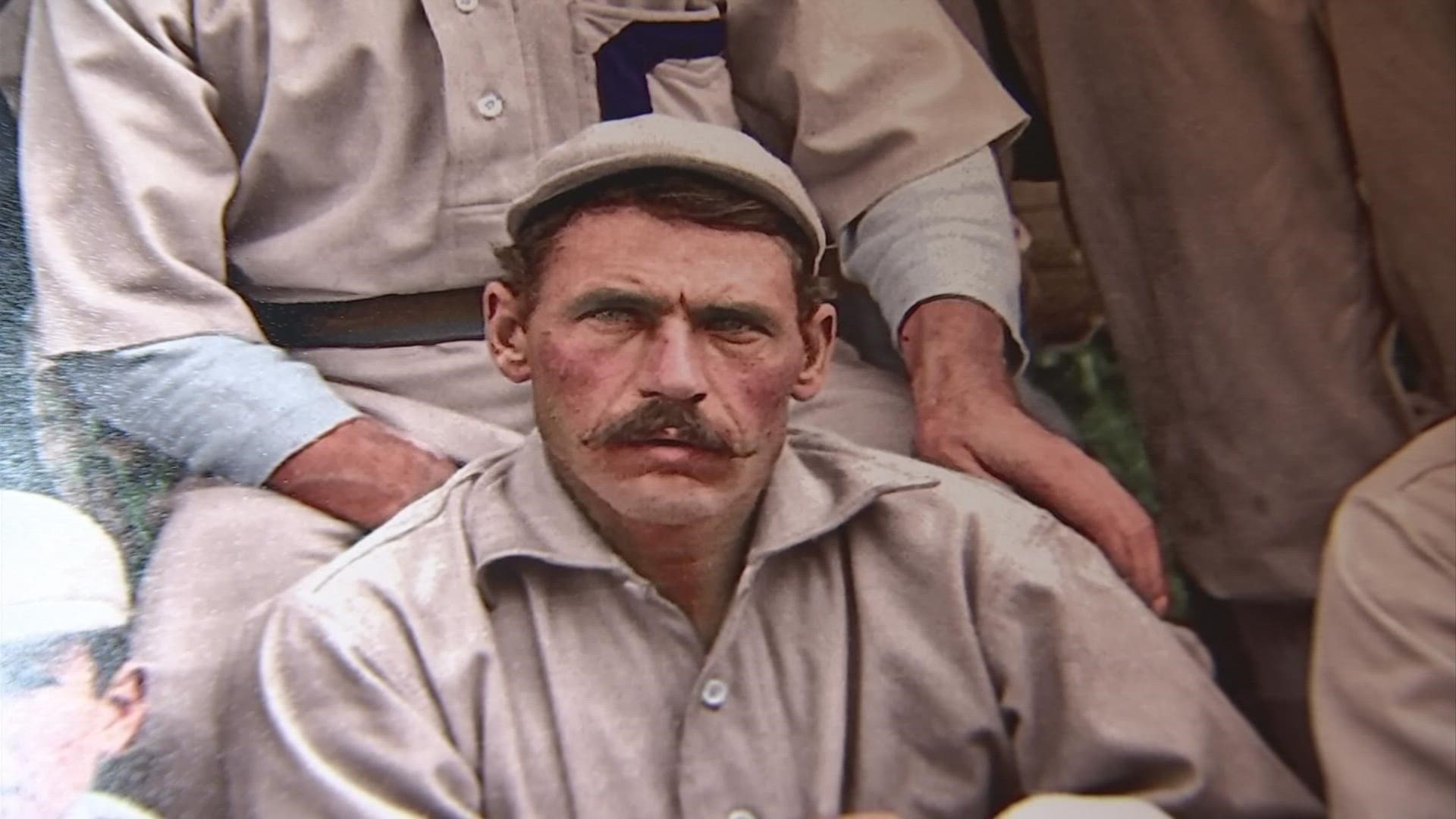

HILLIARD, Ohio — Walk into Steve Sandy’s basement and the era of 1880’s baseball comes back to life.

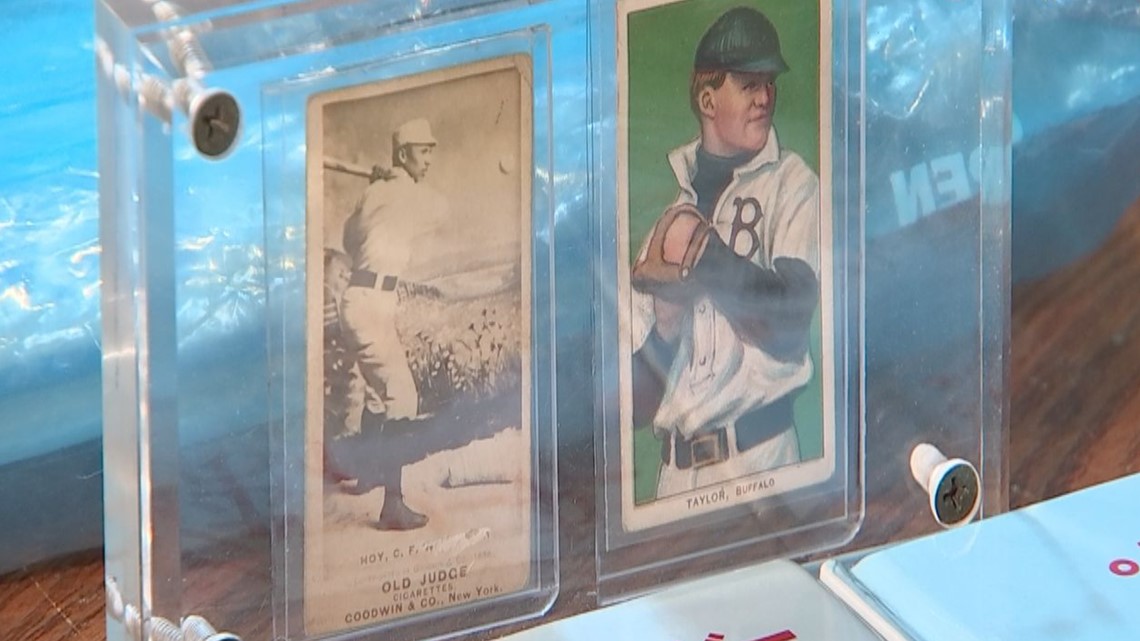

The memorabilia he’s collected is considered unique not only because of its size but because of the player: William Hoy.

The Ohioan is considered by those who followed his career as the greatest deaf player to play the game.

William, who was deaf, was nicknamed “Dummy” which was considered acceptable during the time for people who couldn’t hear.

“I’ve collected everything I could of Hoy,” says Sandy who is also deaf.

William grew up in Houcktown near Findlay. His parents sent him to the Ohio School of the Deaf which at the time was located on Town Street in Columbus before moving to Clintonville.

William would graduate as valedictorian. Because of his size, he stood just 5 feet 4 inches, he was considered too small to play baseball.

So how does a small deaf boy grow to become one of professional baseball's greatest players? He could run.

“My god as a rookie he led the major leagues in steals,” says Don Hoy, a cousin of William's and one of his last living relatives.

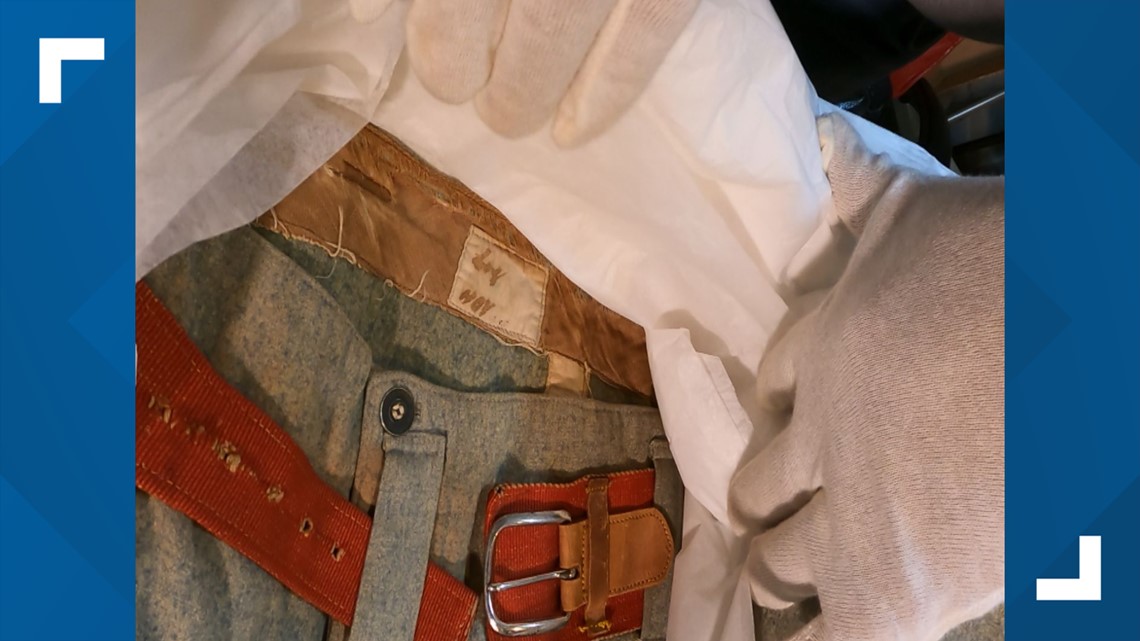

But it’s in Sandy’s basement where you begin to understand the legend. It begins with a piece of his collection he’s never shown to anyone outside his home.

Covered by a black garbage bag and tucked inside a box that Sandy uses white gloves to handle is believed to be the only complete uniform — pants and shirt-that William wore for the Chicago White Sox in 1901.

“Other people have the pants, but not the shirt,” says Sandy.

As Sandy slowly unfolds the uniform he points to the pants.

“You can still see the dirt where he slid. I told the major league hall of fame that I have the shirt and the pants and they did not believe me. They were gobsmacked they couldn't believe I had the complete uniform,” he said.

William wasn’t born deaf. Like many children during his time, he contracted meningitis and lost his hearing at age 3.

Despite never hearing the crack of a bat or a single cheer from the crowd, William’s professional baseball career spanned 14 seasons.

William began his major league career in 1888 with Washington of the National League. A left-handed batter and right-handed thrower, he played with Buffalo, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Chicago and Louisville.

All told, he played in 1,797 games with an average of .288 that included 2,048 hits, 1,429 runs, 40 homers and 725 runs batted in. Known as a great base stealer with tremendous speed, he is credited with 596 steals.

William is one of three outfielders to throw out three base runners at home plate in one game. On June 19, 1889, he threw perfect strikes to catcher Connie Mack to throw out runners attempting to score from second base.

As a Cincinnati Red, William ranks fourth on the club's all-time list for career on-base percentage at .392, 17th all-time in stolen bases with 176, and 30th in franchise history with a .293 career batting average.

The Reds inducted him into their Baseball Hall of Fame in 2003. Yet, his statistics never seemed good enough for the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame.

“It would be an honor to see him in the hall of fame just to honor those with disabilities playing major league baseball,” Sandy said.

This is why for the past 32 years Sandy has tried, unsuccessfully, to get Hoy into the Hall of Fame.

“Whether he gets into the hall of fame that is such a political thing anymore. They don't really look at the value, of the character of the player. It's a numbers game,” Don said.

While his stats are impressive, those who decide on who gets into the MLB Hall of Fame have struggled to compare the game he played versus how the game is played today.

“It is difficult to compare him to modern-day players because during his time going from first to third or second to home on a single was considered a steal. This rule was in effect from 1886 to the end of the 1897 season,” according to Society for American Baseball Research.

But William was more than just a player who collected impressive statistics. Hoy’s inability to hear helped change the game.

“In large stadiums, you can't hear the calls of the ball and the strikes, but you can see the signs and so he introduced it. I would not say he created the signs, but he introduced them,” said Sandy.

William would teach his teammates sign language so he would know if the pitch was a ball or a strike. His base coaches would tell him to run, stop or slide all using hand signs. Those signs are still used today.

“You can't learn sign language without being around a deaf person,” said Sandy.

During his life, William never took credit for introducing hand signs to the game, but many believe he played a significant role in helping hand signs become popular as he played for many teams across the country.

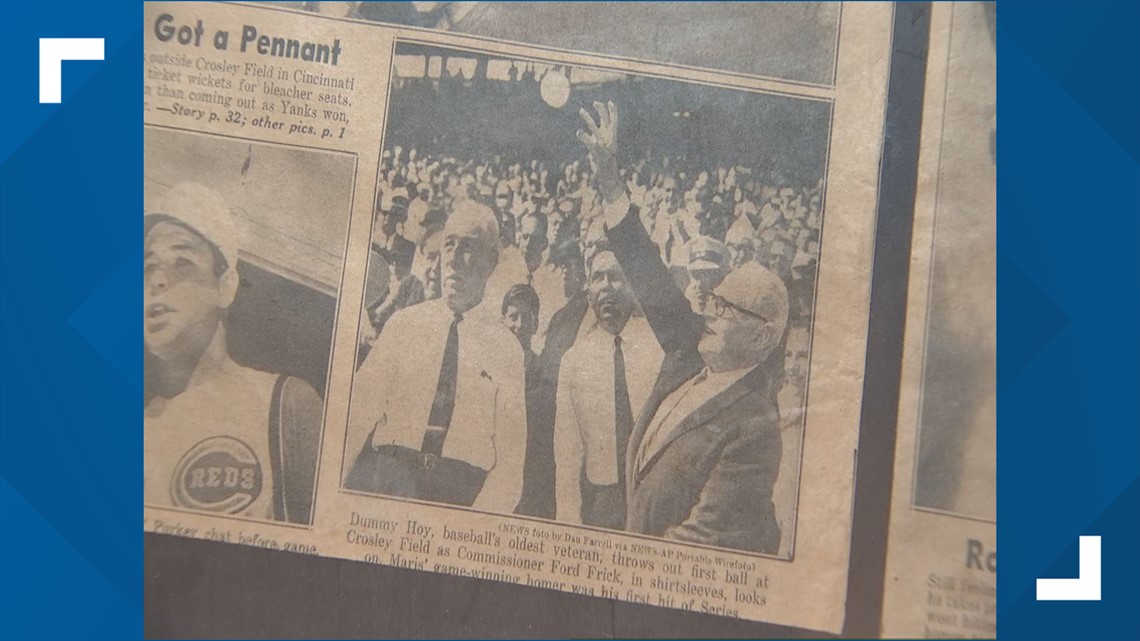

Ultimately, Major League Baseball's Early Baseball Era Committee members will decide if he is Hall of Fame worthy. They meet every 10 years and he has never made the cut.

The committee will meet for the first time this winter to consider long-retired players for election to the Hall of Fame.

When William retired from baseball in 1903, it made him one of 19 players to play in four major leagues. He died in 1961 at the age of 99-years old.

For Sandy, he says it’s time the Hall of Fame recognizes enshrines William in the Hall of Fame, not just because of what he did on the field, but what he gave to the game by passing along sign language which became the language of the game.

“I want Hoy to be inducted and I will have peace with myself,” he said.