WASHINGTON — Stark repudiation by federal judges he appointed. Far-reaching fraud allegations by New York’s attorney general. It's been a week of widening legal troubles for Donald Trump, laying bare the challenges piling up as the former president operates without the protections afforded by the White House.

The bravado that served him well in the political arena is less handy in a legal realm dominated by verifiable evidence, where judges this week have looked askance at his claims and where a fraud investigation that took root when Trump was still president burst into public view in an allegation-filled 222-page state lawsuit.

In politics, “you can say what you want and if people like it, it works. In a legal realm, it’s different,” said Chris Edelson, a presidential powers scholar and American University government professor. “It’s an arena where there are tangible consequences for missteps, misdeeds, false statements in a way that doesn't apply in politics.”

That distinction between politics and law was evident in a single 30-hour period this week.

Trump insisted on Fox News in an interview that aired Wednesday that the highly classified government records he had at Mar-a-Lago actually had been declassified, that a president has the power to declassify information “even by thinking about it.”

A day earlier, however, an independent arbiter his own lawyers had recommended appeared skeptical when the Trump team declined to present any information to support his claims that the documents had been declassified. The special master, Raymond Dearie, a veteran federal judge, said Trump's team was trying to “have its cake and eat it,” too, and that, absent information to back up the claims, he was inclined to regard the records the way the government does: Classified.

On Wednesday morning, Letitia James, the New York State attorney general, accused Trump in a lawsuit of padding his net worth by billions of dollars and habitually misleading banks about the value of prized assets. The lawsuit, the culmination of a three-year investigation that began when he was president, also names as defendants three of his adult children and seeks to bar them from ever again running a company in the state. Trump has denied any wrongdoing.

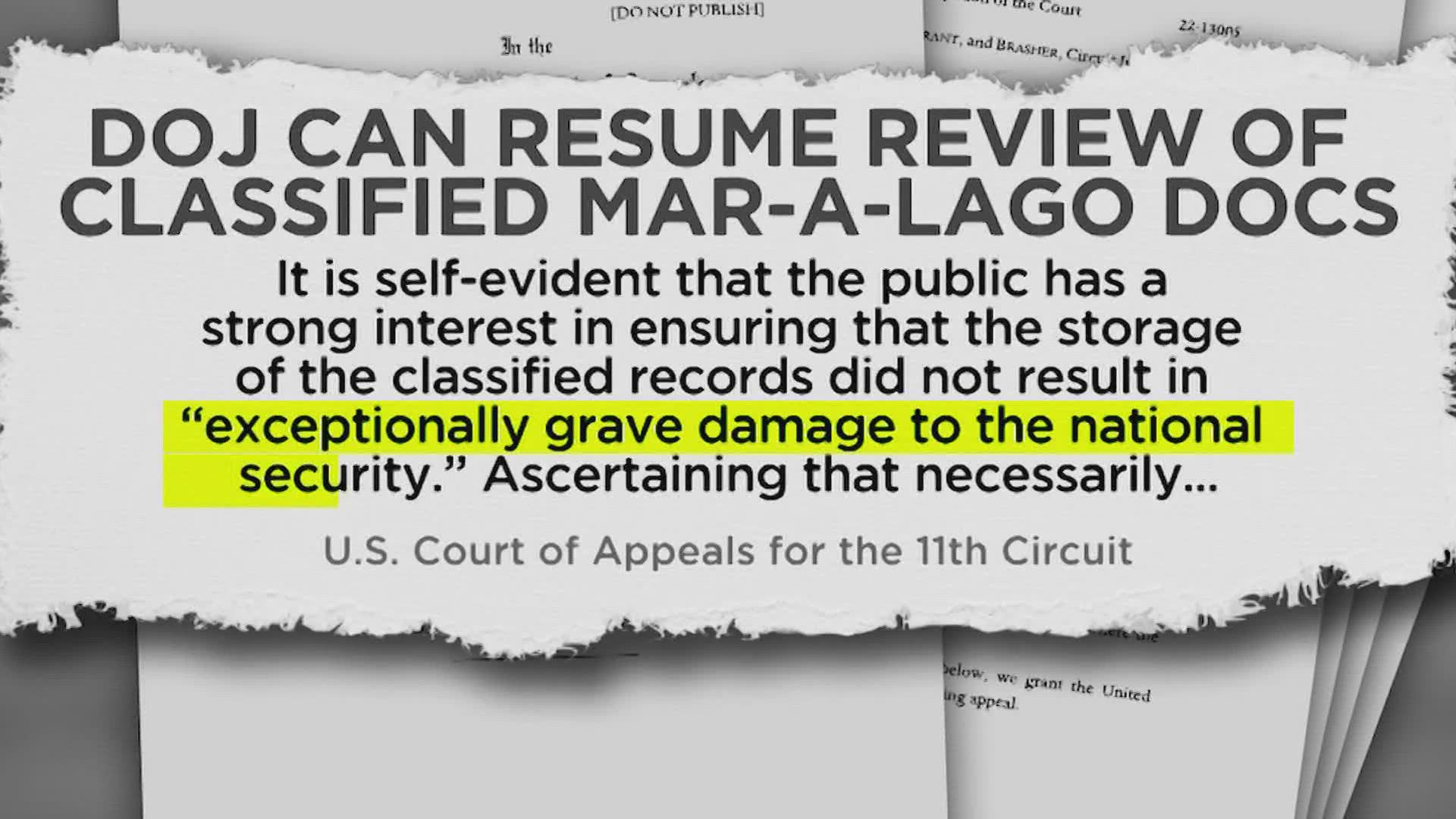

Hours later, three judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit — two of them Trump appointees — handed him a startling loss in the Mar-a-Lago investigation.

The court overwhelmingly rejected arguments that he was entitled to have the special master do an independent review of the roughly 100 classified documents taken during last month's FBI search.

That ruling opened the way for the Justice Department to resume its use of the classified records in its probe. It lifted a hold placed by a lower court judge, Aileen Cannon, a Trump appointee whose rulings in the Mar-a-Lago matter had to date been the sole bright spot for the former president. On Thursday, she responded by striking the parts of her order that had required the Justice Department to give Dearie, and Trump's lawyers, access to the classified records.

Dearie followed up with his own order, giving the Trump team until Sept. 30 to identify errors or mistakes in the FBI's detailed inventory of items taken in the search.

Between Dearie's position, and the appeals court ruling, “I think that basically there may be a developing consensus, if not an already developed consensus, that the government has the stronger position in a lot of these issues and a lot of these controversies,” said Richard Serafini, a Florida criminal defense lawyer and former Justice Department prosecutor.

To be sure, Trump is hardly a stranger to courtroom dramas, having been deposed in numerous lawsuits throughout his decades-long business career, and he has demonstrated a remarkable capacity to survive situations that seemed dire.

His lawyers did not immediately respond Thursday to a request seeking comment.

In the White House, Trump had faced a perilous investigation into whether he had obstructed a Justice Department probe of possible collusion between Russia and his 2016 campaign. Ultimately, he was protected at least in part by the power of the presidency, with special counsel Robert Mueller citing longstanding department policy prohibiting the indictment of a sitting president.

He was twice impeached by a Democratic-led House of Representatives — once over a phone call with Ukraine's leader, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the second time over the Jan. 6, 2021, riot at the Capitol — but was acquitted by the Senate on both occasions thanks to political support from fellow Republicans.

It remains unclear if any of the current investigations — the Mar-a-Lago one or probes related to Jan. 6 or Georgia election interference — will produce criminal charges. And the New York lawsuit is a civil matter.

But there's no question Trump no longer enjoys the legal shield of the presidency, even though he has repeatedly leaned on an expansive view of executive power to defend his retention of records the government says are not his, no matter their classification.

Notably, the Justice Department and the federal appeals court have paid little heed to his assertions that the records had been declassified. For all his claims on TV and social media, both have noted that Trump has presented no formal information to support the idea that he took any steps at all to declassify the records.

The appeals court called the declassification question a “red herring” because even declassifying a record would not change its content or transform it from a government document into a personal one. And the statutes the Justice Department cites as the basis of its investigation do not explicitly mention classified information.

Trump's lawyers also have stopped short of saying in court, or in legal briefs, that the records were declassified. They told Dearie they shouldn't be forced to disclose their stance on that issue now because it could be part of their defense in the event of an indictment.

Even some legal experts who have otherwise sided with Trump in his legal fights are dubious of his assertions.

Jonathan Turley, a George Washington University law professor who testified as a Republican witness in the first impeachment proceedings in 2019, said he was struck by the “lack of a coherent and consistent position from the former president on the classified documents.”

“It’s not clear," he added, “what Jedi-like lawyers said that you could declassify things with a thought, but the courts are unlikely to embrace that claim."