WASHINGTON — The federal government has no legal way to dispose of certain nuclear waste, forcing sites around the country to hold onto their radioactive waste and risking widespread environmental damage or the creation of a "dirty bomb," according to a new report from a government watchdog.

A report released last week by the U.S. Government Accountability Office outlines the issue simply:

"The federal government is responsible for disposal of certain low-level radioactive waste, including greater-than-Class C (GTCC) waste. This waste, which is commercially generated, does not currently have a legal disposal option."

So what exactly is "greater than Class C waste" and why can't it be disposed of?

To put it simply, GTCC waste is the most dangerous form of "low-level" radioactive waste. Within the category are radioactive metals from decommissioned commercial nuclear plants and nuclear materials sealed in industrial or medical equipment (such as the radioactive dye used in some medical procedures).

Some, but not all GTCC waste contains manmade elements heavier than uranium on the periodic table, making that material especially hazardous and long-lasting.

Another category, GTCC-like waste, comes from federal activities such as environmental cleanups, space exploration and government-run nuclear facilities. In essence, it's treated the same as GTCC waste.

Compared to the less dangerous classes: A, B and C, GTCC waste has a higher concentration of radioactive material and decays slower, over hundreds of thousands of years.

The U.S. Department of Energy, which is responsible for storing nuclear waste, has a rough estimate of how much GTCC waste is out there.

In 2010, the department estimated that about 1,100 cubic meters of waste had been produced in the U.S. — enough to fill about 40% of an Olympic swimming pool. By 2083, the Department of Energy says that number will balloon to 12,000 cubic meters of waste. That's enough to fill five Olympic pools.

But the GAO report points out that there is a lot of uncertainty associated with those numbers, partly because there is no national tracking database for sealed sources of GTCC waste, like medical equipment, and because the DOE's projections aren't clear on how they estimate the amount nuclear waste that will come from environmental cleanup sites in the coming decades.

Because policymakers and Congress use those numbers to determine which disposal options are viable, the fact that the information is shrouded in uncertainty makes it more difficult to find a path forward.

After the GAO pointed out the limited useability of the 2010 numbers, the Department of Energy promised to update its procedures for future estimates.

But in a catch-22, officials with the department told the GAO that they had no plans to make new estimates about how much GTCC waste is around until a disposal site has been secured.

"DOE officials told us they do not plan to update the 2010 estimated inventory until a disposal facility applies for a license to dispose of GTCC and GTCC-like waste," the report reads.

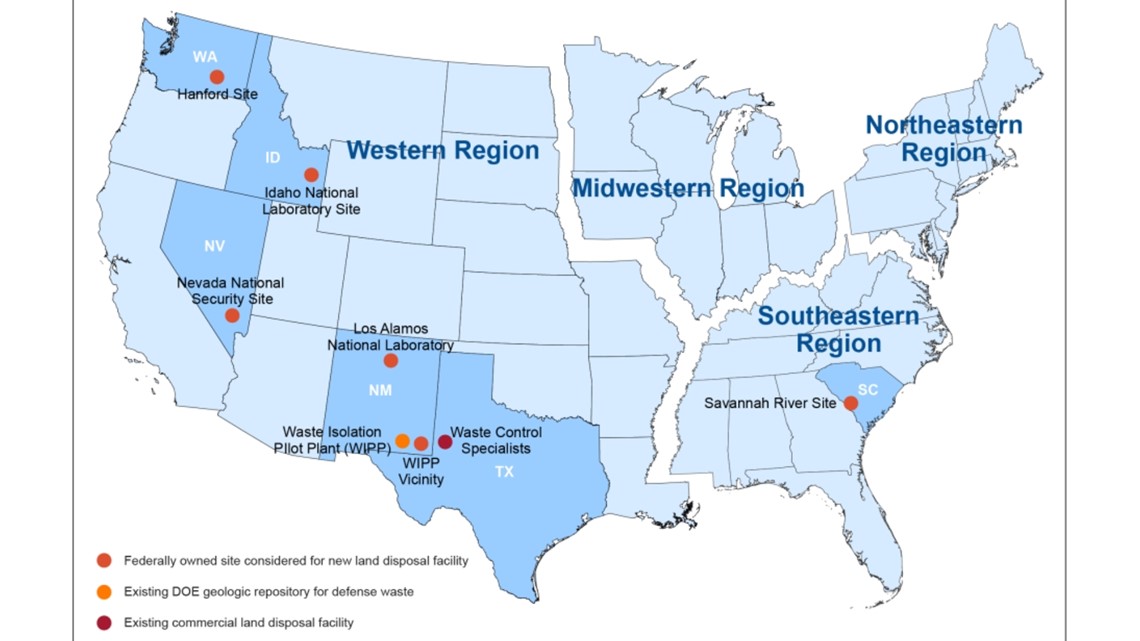

Currently, the U.S. has four locations scattered across the country that are designated as disposal sites for low-level waste.

These four sites, located in Washington state, South Carolina, Utah and Texas, are used as repositories where much of the low-level radioactive waste — such as contaminated filters, rags, medical tubes or syringes. Essentially, these sites bury the nuclear waste to allow it to decay without impacting the environment at large.

Federal regulations say that GTCC waste can't be disposed of in the same way, so none of the four sites are licensed by the states they reside in to take GTCC materials.

And the only "geological repository" — essentially a much deeper form of storage — in the U.S. is the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico. But that repository only accepts waste generated from the development and testing of nuclear weapons.

With all underground storage facilities legally cut off, the most hazardous kind of common nuclear material has nowhere to go. Instead, it's either stored at the site where it was generated or at an above-ground storage facility.

According to the GAO report, this non-permanent storage solution leads to a host of potential problems.

The most likely concern is that improper or above-ground storage for nuclear waste could lead to contamination of the environment around the storage facility. Radiation pollution drastically raises the risk of cancer, according to the EPA, and low-level doses aren't as easy to notice because they don't cause immediate health problems.

And it's not an empty threat. A recent ProPublica investigation revealed a "death map" in a New Mexico town where residents had been poisoned over decades by waste from Cold War-era uranium mines nearby, causing many to die from cancer.

But the GAO report also hinted at a more sinister threat posed by the inability to dispose of radioactive waste:

"For example, sealed sources pose a threat to national security because they can be used to make explosive devices known as dirty bombs," the report reads.

A "dirty bomb" is a type of weapon that combines conventional explosives such as dynamite and nuclear material to spread radiation over a small distance. None have ever been used, although health departments for large areas like New York State have prepared for such an attack.

The Department of Energy identified several sites that could serve as permanent homes for GTCC waste in a 2016 environmental impact statement.

But fixing the problem isn't as easy as having the Department of Energy pick a disposal site, because none of their proposed sites are legally useable for a variety of reasons.

Ideally, the Department of Energy would use the WIPP facility as a disposal site. But that would require a change in the law that would allow that facility to take waste from sources other than nuclear bomb production.

Using any of the existing four facilities that accept low-level nuclear waste would require new infrastructure such as bore-holes and additional measures to prevent access to the nuclear material for at least 500 years. It would also require changes to state and federal regulations to allow their use.

Similarly, developing a new site specifically to store GTCC waste would require cutting through a massive amount of red tape at both the state and federal level.

One major hurdle is the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which mandates that Congress must approve a plan of action for nuclear waste disposal. That means it's up to Congress to pass a law that would either specify where the federal government can dispose of this kind of waste.

No legislation addressing the disposal of GTCC waste appears to have been submitted during the current session of Congress.

When asked for comment about the legislative hurdles to GTCC waste cleanup, the Department of Energy pointed to the statement it sent to the GAO's office concurring with the report's findings: that without Congressional action, their hands were tied.

"Without waste disposal capabilities, cleanup cannot proceed," the statement reads.