COLUMBUS, Ohio — From X-ray body scanners to anti-drone technology, the state is ramping up efforts to keep contraband out of Ohio prisons as drugs and other illicit goods flood inside, even when visitation was curbed during the pandemic.

The anti-contraband measures are aimed at anyone who enters prisons, whether inmates returning from an outside assignment, visitors or staff members, said Annette Chambers-Smith, director of the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction.

“Every time we solve one thing we have to build a better mouse-trap for the next thing,” Chambers-Smith told The Associated Press.

The scope of the problem was underscored last month when federal authorities announced the arrest of a South African woman on suspicion of helping smuggle hundreds of sheets of drug-soaked paper into at least five Ohio prisons. The woman is accused of soaking papers in legal correspondence, which is exempt from normal inspection routines.

The state said it conducted about 1,000 drug seizures a month in state prisons from March through September 2020. Numbers slowly decreased through 2021 and now average just under 500 a month, according to state data.

Among recent initiatives by the Department of Rehabilitation and Correction:

— Installing 15 X-ray body scanners, one per prison, at an initial cost of $1.7 million per machine, paid for by federal CARES Act dollars, with a plan to implement them in all 28 prisons by year’s end. The machines can detect items such as cell phones, drugs, tobacco and weapons.

— Purchasing nine anti-drone detection systems covering 16 of 28 prisons at an annual cost of $1.5 million. Some of the systems cover more than one prison.

— Piloting the use of two hand-held laser scanners costing a total of $48,500 that can identify a substance, and installing more exterior fences meant to stop “fence throws,” or people tossing contraband over the security fences.

— Digitizing all incoming inmate mail other than legal mail, a program announced last year but still not implemented. The program, with a $22.7 million annual cost, is now expected this summer. Its goal: stopping the practice of outsiders sending inmates paper soaked with synthetic narcotics such as K2. In the interim, the state photocopies all mail except legal correspondence.

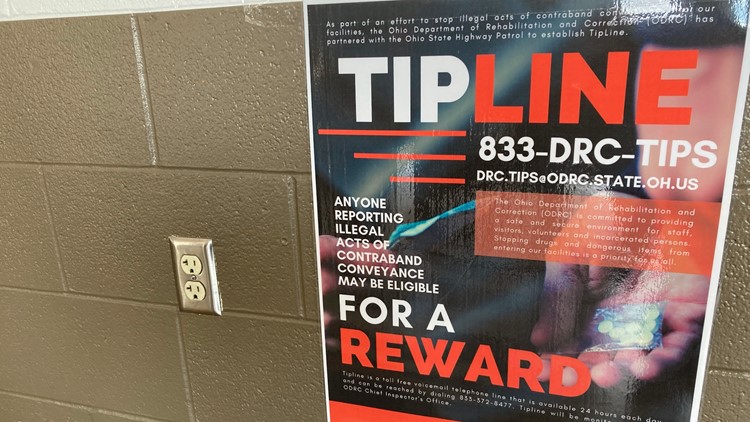

— Partnering with the state patrol to create a tip phone line and email address for an initiative dubbed “Know Something? Tell us,” that offers possible rewards for reports of contraband.

Inmates interviewed by the AP say the current drugs of choice are strips of suboxone, a drug that can be used to reduce dependence on opioids, and K2 — or “tune” as it's known on the inside.

Prisoners often smoke the K2 ingested paper, producing a strong, burnt popcorn smell. Inmates say the paper couldn't be detected by scanners, and often comes via other sources, including staff.

“It’s kind of moot to put these scanners in place because it’s not going to thwart the problem,” said Jermane Scott, 44, serving a life sentence at Mansfield Correctional Institution for aggravated murder.

Inmate advocates say the prisons are already awash in easily attainable drugs and the money would be spent better on more efforts to fight substance abuse.

“We have people going in with no drug addictions and coming out drug addicts,” said Jeanna Kenney, the wife of an inmate and president of Ensuring Parole for Incarcerated Citizens.

In 2017, a former guard at Lake Erie Correctional Institution pleaded guilty to one count of drug possession after his indictment the year before on charges of plotting to smuggle suboxone strips into the prison.

“You can shake me down all day, you’ll never find these subs (Suboxone),” the former guard told an undercover agent during a controlled buy in 2016, according to an Ohio State Highway Patrol investigative report obtained by the AP.

In 2019, a corrections officer at Belmont Correctional Institution in eastern Ohio was sentenced to 30 months in federal prison for smuggling tobacco and drugs — including suboxone — into the prison over a three-year period.

In October 2020, eight months into the pandemic, a Marion prison guard was apprehended after bringing in 23 pieces of paper soaked in K2. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to a year in prison.

Those guards represent “a couple of bad actors as you have in any other organization or employer,” said Chris Mabe, president of the union that represents Ohio prison guards. Fighting contraband should involve more hiring, he added.

“The best way to stop things from happening in a prison is to have more staff,” Mabe said.

Employees and inmates aren't the only ones bringing contraband into Ohio prisons.

Last year, two men were indicted for allegedly using a drone to drop drugs and cell phones into the yard at Warren Correctional Institution.

In 2018, a milk deliveryman was sentenced to house arrest after he was accused of hiding marijuana, tobacco and cellphones inside milk cartons and smuggling them into Lebanon Correctional Facility.

In 2010, the state watchdog found inmates working at the governor's residence in suburban Columbus were able to smuggle tobacco dropped off near the home into the smoke-free prisons, where it was sold to other inmates.

With the purchase of the X-ray body scanners, Ohio joins other states using similar machines in prisons, including Mississippi, which last year spent $1.1 million in federal pandemic aid dollars on 11 body scanners.

Beginning in 2016, California installed nearly 1,000 sophisticated metal detectors, scanners and secret security cameras at its prisons in its latest attempt to thwart the smuggling of cellphones, thousands of which flooded the prisons despite previous efforts.

Virginia has taken the opposite approach as Ohio with its X-ray scanners, using them mainly to screen staff and visitors and occasionally inmates, said Benjamin Jarvela, spokesperson for the state corrections agency.

“The primary purpose here is to keep contraband and dangerous items from coming in, so they are primarily used to screen individuals entering the facilities,” he said.

But in Ohio, the state's new X-ray body scanners will screen only inmates returning from outside assignments such as highway litter pick-up or medical appointments. State rules only permit the scanners to be used on inmates, Chambers-Smith said.

The machines will reduce physical contact between staff and inmates, a need driven home by the pandemic and are more effective than a strip search, she added.

“When these machines get put in place, we’ll be able to scan and then get a lot more information than we get from just taking their clothes off,” Chambers-Smith said.