Why is it people are so afraid of asking for help?

It’s a crutch. It’s a hand-me-out. It’s a sign of weakness.

But not today.

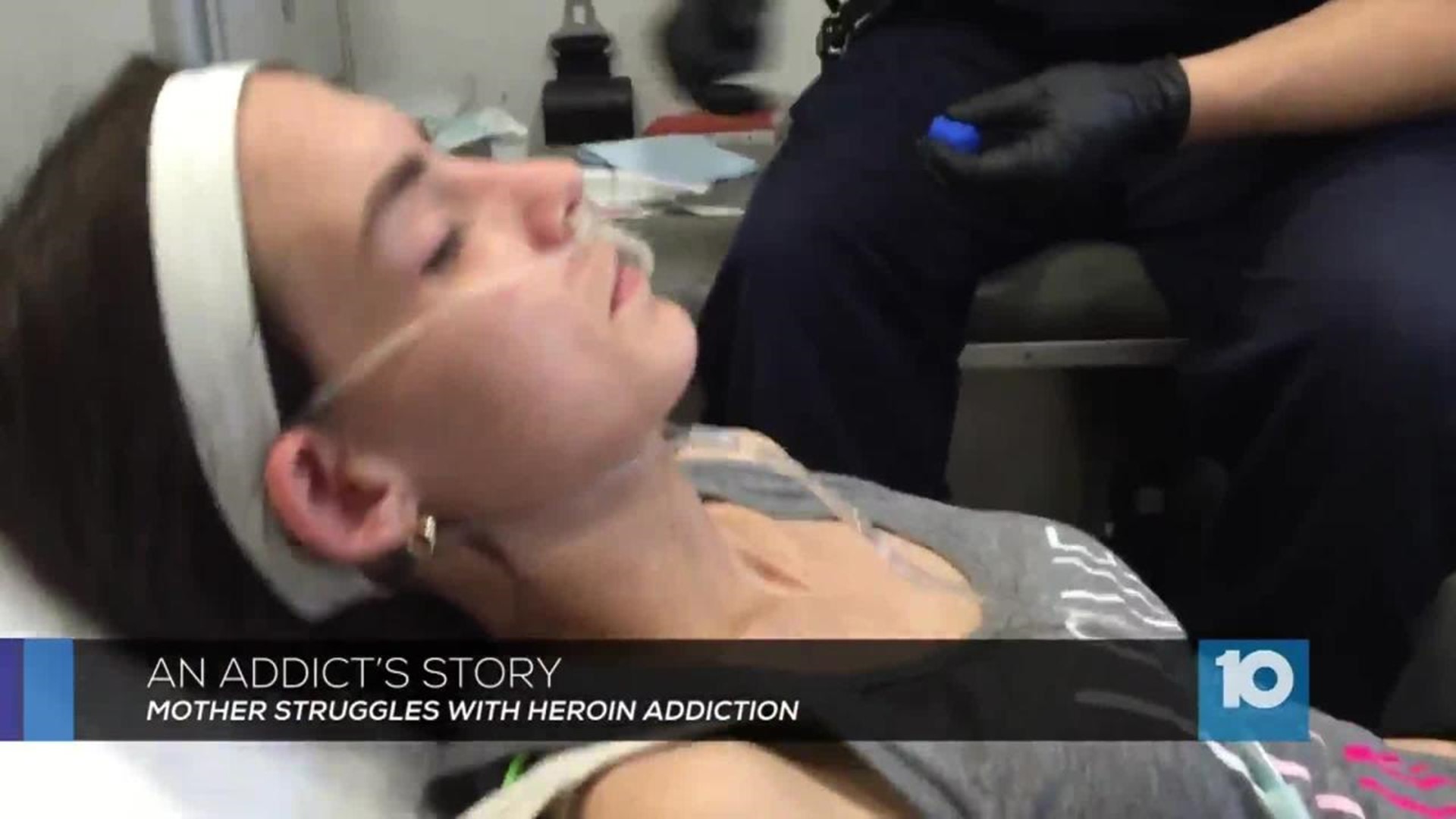

24-year-old Crysta Joehlin is crying out for help. On a warm morning on the next-to-last day in August, Joehlin walked into the Newark Police Department and metaphorically waved a white flag of unconditional surrender; a desperate cry for help from a heroin addict.

“She wants to do this,” Crysta’s mother, Cathy said. “She wants to be better.”

Two years ago after giving birth to her daughter, Joehlin started having hip pains. Doctors prescribed Vicodin. After about a year – they took her off it.

“She started going off the street to buy them,” Cathy said.

Joehlin was addicted.

The streets offered her answers. First, pills. Then, heroin. One day in August Cathy got the call that no mother wants to answer.

“She said she felt like she couldn’t breathe and she was coughing and then she woke up and the person was doing CPR on her,” Cathy said.

“And the guy beside me was shooting up,” Joehlin said. “[He] didn’t even care.”

Crysta had overdosed and believes she died.

In a small, low-lit waiting room just outside the Emergency Room at Licking Memorial Hospital, Cathy, and Joehlin’s step-father, Shawn Wilcox clasp hands and re-live the pain and heartache of that day.

They’re no more than 100 feet from their daughter, but they feel worlds apart.

“Oh, yeah,” Cathy said. “She told us – she said she died.”

“Five days ago I almost overdosed and died,” Joehlin said.

It’s the moment Joehlin knew she needed to ask for help.

“And, as soon as she walked through my doors, she was straight on the phone with rehab centers, begging for somebody to help her,” Cathy said.

“She said ‘Dad, if I leave here without help today, I’ll die’,” Wilcox said. “No one wants to hear their child say that.”

Optimistic minutes turned to hopeless days.

“She tried for a week to call rehab centers, by herself,” Cathy said. “She had a notebook this thick being turned away.”

But then, a program; a helping hand stretched out from a drug addict’s unlikely ally.

“Recovery’s not easy,” Newark Police Chief Barry Connell said. “We’re finding that out every day.”

It’s why Connell started the Newark Addiction Recovery Initiative (NARI). The program essentially allows addicts to walk through the front doors of the police station and seek help with no criminal consequences.

“It seemed odd for [drug users] to walk into a police department and ask for help,” Connell said.

But it is happening. A lot.

Almost 40 addicts have taken up the offer since June. Some, like Joehlin, have no insurance at all. At least for now the city sees the benefit to paying the bill.

“If, ultimately, the folks that we’re helping…they actually become a ‘productive member of society’…they can enjoy this community and make things better,” Connell said.

The program does have stipulations regarding who is eligible, however.

A person seeking help cannot be a sex offender, convicted of a violent felony or convicted of a felony offense in the last 12 months including drug related, theft or fraud. Applicants also cannot have a misdemeanor violence offense within the last year including assault, battery or domestic violence. Applicants cannot have a misdemeanor charge within the last year with offenses including driving under the influence, simple drug possession or disorderly conduct.

Joehlin says she is thankful for the opportunity to get clean.

“I want to say thank you,” she said. “I definitely would not be able to get clean for myself or for my daughter without [the Newark Police Department]. And, if I didn’t get this help I probably would be dead.”

She’s trying to let go of who she was while hoping to hold on to what made her “her” in the first place.

Before going to detox at Shepherd Hill in Newark, Joehlin cried tears of gratitude and relief while her mother and Wilcox hovered over her, offering words of encouragement.

“Everybody that goes through this world goes through things that they wish they didn’t,” Cathy said to her daughter. “But, that’s what life is about.”

Learning to accept failure, to recognize opportunity, to be brave and to try.

“Yeah, it’s scary,” Joehlin said. But, I mean, who isn’t? But you have to take that step or you’ll never know. You have to try.”

When you really think about it the only thing that is truly decided by individuals: the choices that are made, no matter how difficult.

“I think I want others to know that there is help out there if you really want it,” Joehlin said. “You have to want it. I’m determined right now. I’m ready to do this and I want to recover for myself.”

The choice for Joehlin came at, arguably, her lowest point.

“I have no idea what I’m up against,” she said. “I’ve never withdrawn from heroin like this. This [NARI] program that they have is very amazing and it gives people great opportunity. But, like I said, you have to want it.”

An opportunity. A choice. An addict’s difficult choice to turn down that is just as difficult to accept.

After detoxing for four days at Shepherd Hill in Newark, and after being offered a 28-day stay at a local treatment facility, Joehlin opted out.

An unfortunate choice that unfortunately is all too familiar.

“Yeah, I’d call myself a drug addict,” Justin Huntzinger said.

It started when Huntzinger was 12. He’s now 22.

“I’m lost…for real,” he said.

He’s lost in a vicious, endless cycle of drugs; pills, cocaine, crack, meth and heroin.

“The heroin was the most,” he said. “It was every day. I would only do other drugs if I could do them for free.”

A constant struggle. A constant choice.

“I don’t want to keep doing dope, but then again, I don’t really know what else to do, sometimes,” he said.

Huntzinger found sobriety only during multiple stays in jail or endless, failed attempts at rehab. In fact, just a couple days before his interview with 10TV, he was accepted to a treatment facility in Dayton.

He was there less than a day.

“Yeah, I regret leaving,” he said. “I definitely should have stayed.”

But choices are like days; even on the worst one – just wait – another will always come around.

About two weeks after the first interview, Huntzinger was given another chance.

“They pretty much gave me a chance, you know what I mean,” he said.

This chance from Serenity Street. It’s a privately funded living facility for recovering addicts, offering a year-long program to get clean and re-establish lives.

“Before they came and interviewed me, I said a prayer,” he said. “Something like ‘Please let me get into Serenity Street’.”

At the time of the second interview, Huntzinger was six days clean.

A new man. A new outlook. An old smile. A forgotten laugh he hadn’t heard in years.

He stays busy – working by selling items through online auction sites and earning money while earning back self-worth.

“I’ve always known what I needed to do,” he said. I’ve just never really had the strength or courage to do it.”

It will be a long road, no doubt, but for now, Huntzinger is reclaiming his life and taking pride in this choice to change.