COLUMBUS, Ohio — Even though Shannon Hardin is City Council president, in his heart he’s still just a kid from Columbus.

“I get really excited being a legacy Columbus kid,” he said. “I think we always felt we were in somebody’s else's shadow.”

Columbus isn’t in the shadows anymore. Central Ohio is growing rapidly, and one million more people are expected to move to the region in the next 25 years.

This story is part of 10TV's "Boomtown" initiative — our commitment to covering every angle of central Ohio's rapid growth. This includes highlighting success stories, shining a light on growing pains and seeking solutions to issues in your everyday life.

That growth comes as the city reinvests in neighborhoods it once neglected, like King-Lincoln Bronzeville where Hardin’s family is from. His grandmother’s home was among 400 knocked down in the 1960s to build Interstate 71. The interstate connects Columbus to the north and south but isolated thousands of people living King-Lincoln and the near east side.

Before the interstate cut through King-Lincoln Bronzeville, about 64,000 people lived in the neighborhood. That number dwindled to 16,000 by 1999.

“It cut off this historically Black neighborhood from Downtown, the success of our community,” Hardin said. “What happened was there became urban decay.”

That urban decay was the effect of redlining, Nicole Sutton said. She is the African American Special Collections Librarian at the Columbus Metropolitain Library and a redlining expert.

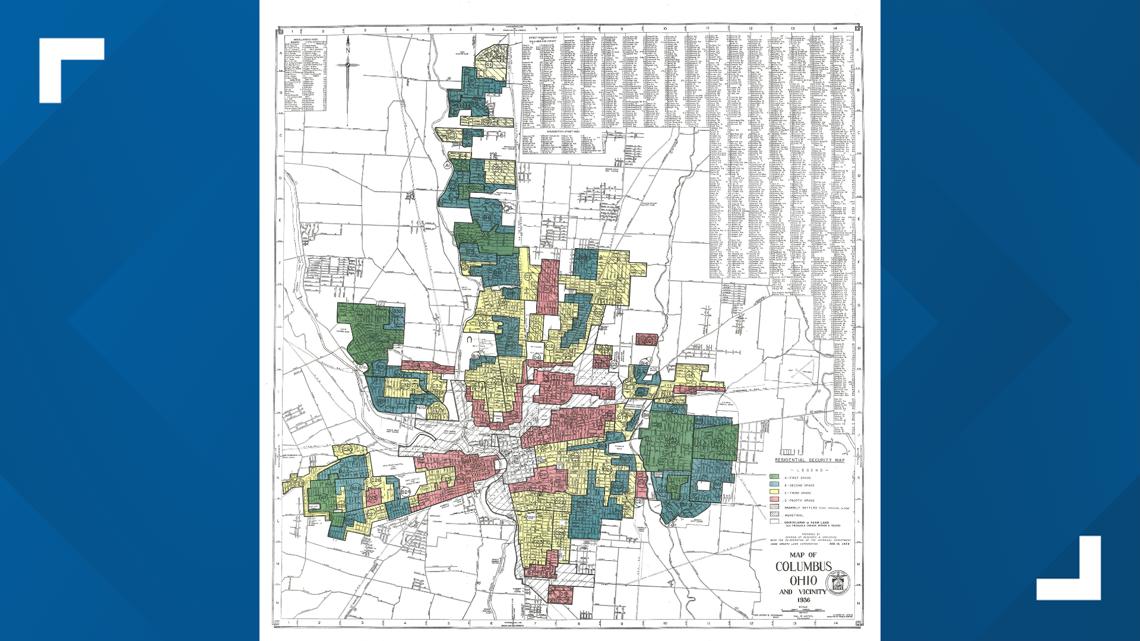

The federal government used a method called redlining to segregate neighborhoods and control homeownership in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s. The Federal Home Owners Loan Corporation was created in the 1930s as part of the New Deal. The corporation’s goal was to refinance mortgages and expand homebuying opportunities. The FHOL categorized neighborhoods as safe or risky for investment by considering the races and ethnicities of the people living in the area. Neighborhoods that were redlined were considered risky for investors because Black people and immigrants lived there.

“All of this was done again by the federal government,” Sutton said. “They thought that they could have racial harmony if they could keep the races separate, and that became a requirement for providing mortgages was if the area was segregated.”

Redlining was outlawed in 1968, but the damage was already done. Research by the Kirwan Institute shows redlined neighborhoods still have higher rates of infant mortality, incarceration, and poverty.

“The story of the Near East Side is one that is similar to a lot of other African American communities around the country,” Hardin said.

A new map will now play a big role in the fate of some of Columbus’ neighborhoods – but this time instead of excluding people, the city wants to invite them in.

The new map is called Zone In and shows the city’s zoning code, which was updated in July for the first time in 70 years. The new code will allow developers to build denser and mixed-use buildings in certain neighborhoods, including places that were once redlined like King-Lincoln Bronzeville. The goal is to create more housing fast and stabilize the city’s rising cost of living.

Hardin also hopes the updated zoning code will attract new development to areas that were neglected, upgrading the quality of life for the people who already live there and the thousands that are expected to move in.

“This is the difference between our forefathers who brought this freeway through and displaced my family,” Hardin said. “We have to be as intentional about including people as maybe our forefathers were about excluding and moving folks out of the way for success.”