COLUMBUS, Ohio — To reconcile with history, you have to face it. But Ohio’s Laotian-Americans face a unique problem; their history is more or less secret.

From 1964 to 1973, the U.S. dropped more than two million tons of ordnance over Laos. Intelligence showed communist guerillas were using the Laotian Ho Chi Minh trail to bring supplies back into Vietnam. The CIA decided to bomb them instead of risking soldiers.

The U.S. dropped thousands of bombs each month. There was roughly one bombing every eight minutes. Much of the country was razed to the ground.

“During the time of the war, the population of Laos was around 2.2 million,” Executive Director of nonprofit Legacies of War Sera Koulabdara said. “About 25% of the population had to flee.”

One mission of Legacies of War is to educate the public about the Secret War.

Many details of the CIA’s Secret War in Laos were only released in the Pentagon Papers in 1971. The CIA also tried to depose the communist Pathet Lao regime in Laos.

U.S. government documents show that about a third of the bombs never exploded. They are still buried in the soil of Laos, exploding under farmers and children. More than 20,000 people have been killed or injured by the unexploded bombs since the end of the war.

“Children mistake these [bombs] as a toy ball,” Koulabdara said. “And they would pick it up and throw it, and it would kill them on impact. Farmers can't farm their land safely. The biggest threats to Laos right now are these American bombs.”

Central Ohio is now home to tens of thousands of Laotian-Americans. Koulabdara said every single one of them has been impacted in some way by the Secret War. Most American schools, however, do not teach about it.

“I never knew how this war that happened decades before I was born could still impact my life today. And it's exactly the same for many Lao Americans who are like me, [who] didn't really know what their parents or grandparents went through,” Koulabdara said.

Laotians who fled the war became refugees in surrounding countries, like Thailand and Vietnam. 10TV spoke to Bounthanh Phommasathit, a survivor of the bombings and former refugee, about her journey.

“Had I not spoken English before, I would be dead,” Phommasathit said. “A lot of people died.”

Phommasathit was a teenager when the U.S. pulled out of the war completely and the communists took over. She said she and her husband lived in poverty until they escaped.

“So in Thailand, there's several refugee camps, north and south. Because of [my husband’s] parents, [we] would live in the south,” Phommasathit said. “So we went to the south. We dressed like we were going fishing and put everything in a canoe. And we went to the border.”

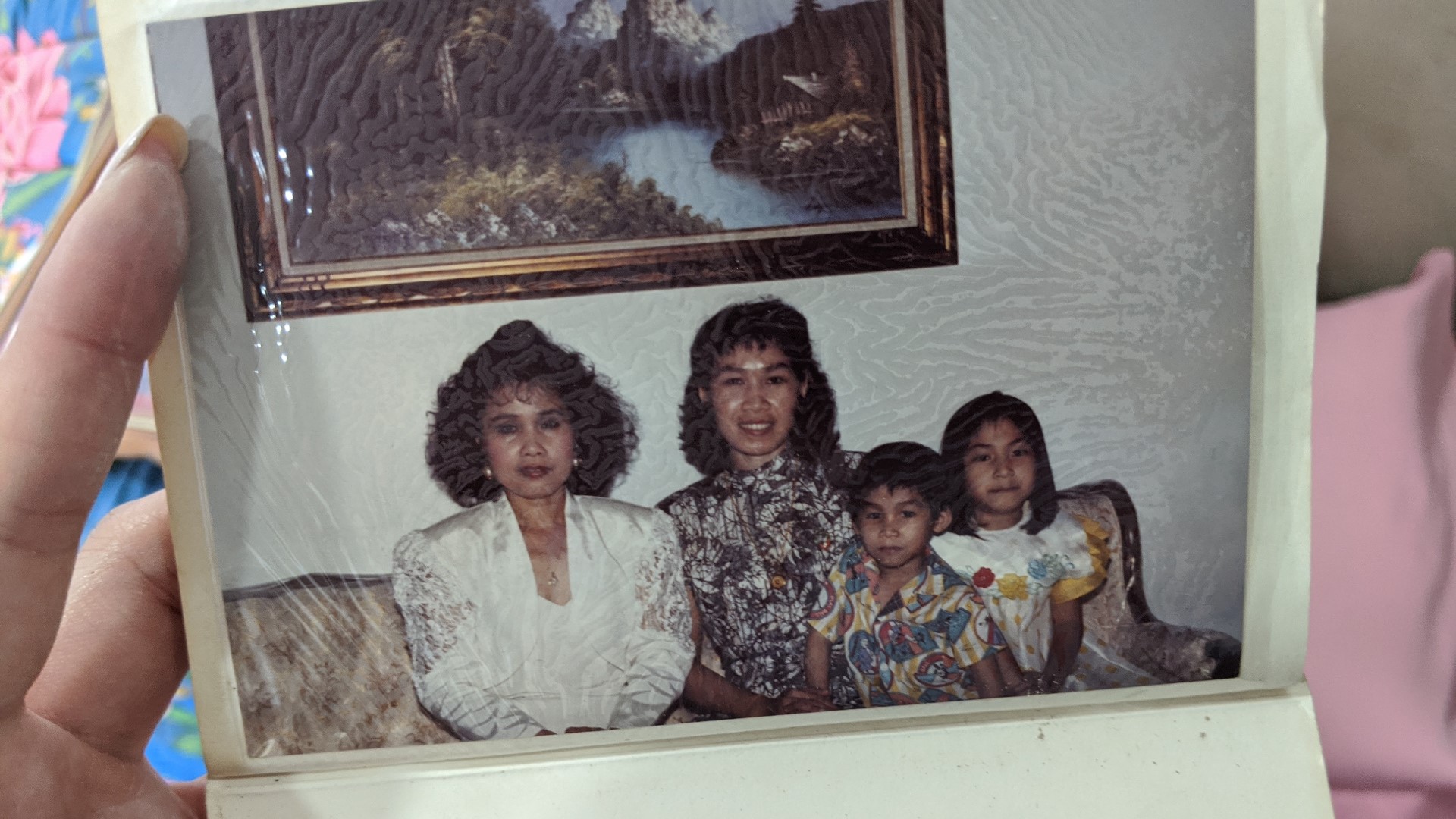

Phommasathit, her husband, and her two children made it to the U.S. in 1979, along with many other Laotian immigrants. She began to work as a social worker and worked her way up. She was on the Ohio Commission on Minority Health and is a co-founder of the nonprofit Laotian Mutual Aid Association. She now volunteers with Legacies of War, serves as secretary for the Buddhist temple Wat Buddha Samakidham and is a board member for the Asian Festival.

Phommasathit said that after all her years here, she sees language as one of the biggest obstacles Laotian refugees have to overcome. She said her years as a social worker showed her a community struggling to reconcile with the war.

The United States, the same country that bombed the Laotian refugees, was now their home.

“This is not the people. It’s the government policy that did it. And why did they do that? It’s unnecessary,” Phommasathit said. “How can we reconcile? We can reconcile between the people. The Lao people and the people of the United States.”

For both Phommasathit and Koulabdara, reconciliation has multiple paths.

Phommasathit has asked for funds to finish the Buddhist temple, build a museum about the Secret War and establish a rest home for Laotian refugees.

“Since they are a silent type of people, they cannot speak English. They probably want to be associated with folks that know the language and end their life in a place that would be comfortable,” Phommasathit said.

Meanwhile, Koulabdara and Legacies of War advocate for congressional cleanup of unexploded ordinances. She tells the story of the Secret War wherever she can because it is her own story.

“It’s about reconciling with our pasts,” Koulabdara said. “It’s providing a place for people to truly talk about it, to make sure this history is told so that we can protect future generations from making the same mistake. Making sure that people know the trauma that they’re feeling, the trauma that their family went through is real.”