COLUMBUS, Ohio — Damara Harris said her son called to say he wanted to come home.

Daimar Bowden, a 17-year old from Columbus, was calling from Lakeside Academy, a Michigan behavioral treatment center where days earlier another teen had died.

Surveillance video from the April 28, 2020 incident shows 16-year-old Cornelius Frederick throwing napkins and food at other teens.

When he did it again in front of staff, he was shoved and then held down in a restraint hold by multiple staff members for more than eight minutes.

When they let up, he was unresponsive and died two days later.

Staff members told authorities Cornelius’ behavior – antagonizing other peers – prompted the restraint and that he was struggling with the staff during it.

Another teen told Kalamazoo Police officers that it looked like Cornelius was having trouble breathing.

In wake of Cornelius’ death, the facility closed, three staff members were criminally charged and kids like Daimar Bowden – and others from across the country – were sent back home.

Back in Columbus, just two months later, Daimar Bowden was fatally shot in the Hilltop area.

Damara Harris said her son’s death involved an altercation over gun with someone he knew.

“Just having him – watching him grow – and then one day he’s not there anymore. It’s not a great feeling. It’s empty a lot,” Damara Harris told 10 Investigates.

Shipped Out

These stories are not unique, but are part of a larger pattern that 10 Investigates uncovered - where children from Ohio are shipped out to behavioral treatment facilities across the country that have been mired by allegations of abuse and neglect.

The children – many of whom are in foster care or recommended by juvenile court – are sent to these facilities seeking help or placement outside of their homes. But critics say they are exposed to more harm than good.

Records reviewed by 10 Investigates show there have been repeated and recurring issues with assaults, alleged sexual abuse and children running away at many of these facilities.

And where the children go – millions of public dollars follow.

A spokesman for the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, which oversees county-run children services agencies, said as of mid-October, 85 Ohio children were currently at out-of-state facilities.

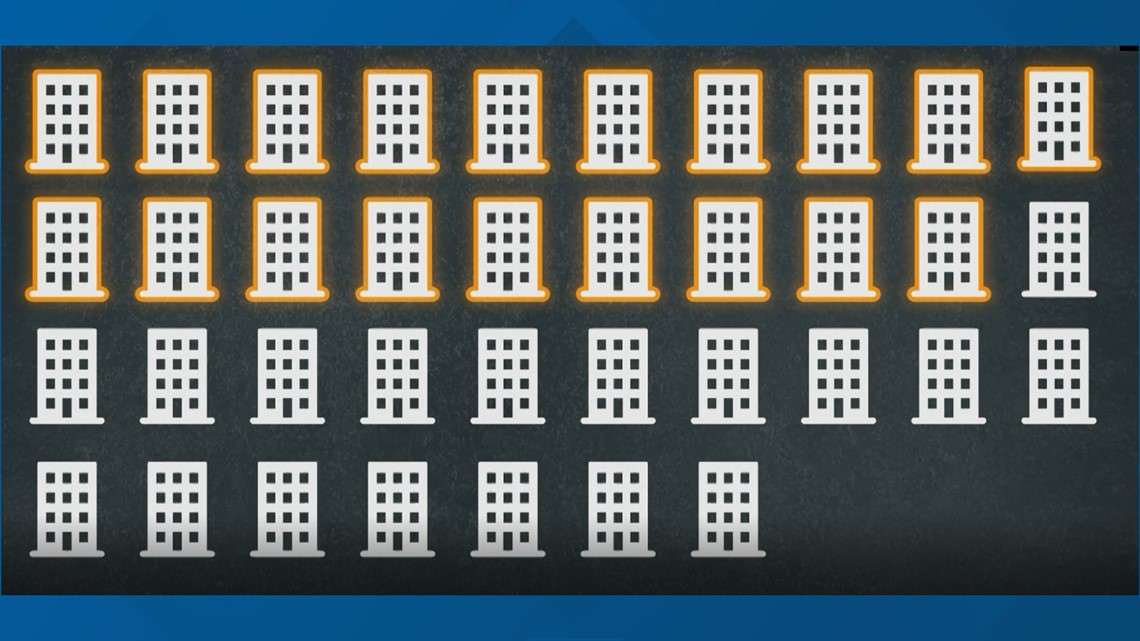

Of the 37 out-of-state facilities that Ohio uses, 10 Investigates found allegations of abuse in more than half of them.

As part of our reporting we examined police reports, inspection records, lawsuits and published news accounts of incidents at facilities in nine different states. We also filed open records requests in several states.

10 Investigates also interviewed parents, past residents, attorneys and a licensed social worker and attempted to speak with other stakeholders – including the operators of these facilities.

Among our other findings:

- Ohio has spent nearly $50 million in public funds over the past five years sending children to out-of-state behavioral treatment facilities, according to a 10 Investigates’ review of Franklin County funds and state Medicaid dollars.

- Nearly $200,000 went to a facility in Indianapolis where a parent told 10 Investigates his adopted son abused others there. A local Indianapolis television station report in 2018 detailed other problems there. Franklin County Children Services says it no longer sends kids to Resource Acquisition Center. A woman who answered the phone there this week directed 10 Investigates’ questions to the parent company, Acadia, and then hung up. The Indiana Department of Child Services has so far not provided incident reports to 10 Investigates, which were sought through an public records request more than a month ago.

- $4.7 million went to Detroit Capstone/Detroit Behavioral Institute, which closed this summer after inspectors with the state of Michigan raised concerns about issues there. Records show in June an Ohio girl admitted that she hit – and then was struck by a staff member. She was returned to Ohio, Michigan inspection records show. Hers was just one of several incidents flagged by the state of Michigan.

- Since 2018, $8.7 million have gone to four different facilities in Arkansas. 10 Investigates found allegations of assaults, restraints that weren’t documented, elopements and allegations of sexual abuse.

10 Investigates also discovered the state of Ohio – and county-run agencies including Franklin County Children Services – have continued to send children to these facilities despite well-documented and publicized reports of recurring reports of abuse and neglect.

In fact, FCCS itself reported some of alleged abuse to authorities.

In December of 2020, FCCS faxed the Faulkner County Sheriff’s Office in Arkansas alleging that a child at a facility there was hurt during an altercation with other teens and that a staff member at that facility witnessed the incident “but did not intervene to stop it.”

U.S. Senate investigation

Two U.S. Senators have raised concerns about the mistreatment of children who are sent to these residential treatment facilities.

Senators Ron Wyden, D–Oregon, and Patty Murray, D–Washington, drafted letters this summer to four major companies – Universal Health Solutions, Acadia, Devereux Behavioral Health and Vivant Behavioral Health (which took over properties formerly operated by Sequel Youth and Family Services and has many of the same executives, according to 10 Investigates’ research).

A message left with Sequel and Vivant founder Jay Ripley was not returned.

Many Sequel facilities were shuttered in recent years – including Sequel Pomegranate here in Columbus and Lakeside Academy in Michigan, which closed following the death of Cornelius Frederick.

Collectively, the earnings of the four companies are in the billions of dollars.

Federal financial disclosure records show Acadia reported third quarter revenue of $666 million. More than half of their revenue, per Security and Exchange Commission filings show, came from public Medicaid dollars.

All four companies operate residential treatment facilities across the country – including some where Ohio children are sent.

The senators’ letters read in part: “While there is a role for (residential treatment facilities) in the continuum of treatment, we are concerned by numerous stories of exploitation, mistreatment and maltreatment, abuse and neglect, and fatalities in these facilities…”

Their senators’ letters referenced “a series of reports” and their reference materials cited the previous reporting of 10 Investigates.

10 Investigates has spent years reporting on problems that have occurred in these facilities in Ohio.

Our reporting led to increased inspections by state and county agencies; eventually, one facility – Sequel Pomegranate – closed in wake of recurring problems with abuse and neglect.

The National Disability Rights Network, referenced in the senators’ letters, cited 10 Investigates’ reporting in its October 2021 report.

NDRN is the parent organization of various state affiliates – like Disability Rights Ohio – which are tasked with investigating the treatment of children in these facilities.

Lawsuits filed against companies

As part of our reporting, 10 Investigates reviewed more than two dozens of lawsuits that have been filed against the companies.

Arkansas attorney Jered Medlock told 10 Investigates he has represented children from across the country who allege they were abused in Arkansas facilities.

“My present child is from Illinois, I had a case for the kid from Ohio, a case with the kid from Maine…” Medlock said. “We've had any number of these cases going for the last five years consistently. There's never been a drop off where we didn't have at least one or two cases going here in the state of Arkansas.”

“Misery Mill”

Stefan Specht lost his mother to suicide when he was two. His father died when he was 14. Growing up in Arkansas, Specht said that he was shipped to a facility out of state and also spent time at residential treatment facilities in Arkansas – including Millcreek of Arkansas, owned by Acadia, a provider that operates facilities where Ohio children have been sent.

“The nickname that some of us had for it was the ‘misery mill,’ you would be there you would be under constant psychological assault, emotional assault, because there were guys there that just it was all about pecking order,” Specht said.

Now in his 20s, Specht has critical of the industry and is calling for better treatment for foster youth.

"The only thing that we can do is make sure that parents are very aware that if they have a child that is experiencing mental illness that they should think twice about sending them to one of these well-marketed facilities.”

Incident reports reviewed by 10 Investigates showed in July of this year a staff member at Millcreek was accused of kicking a child in the face during a restraint. The facility’s own investigation substantiated the claim.

A report from August shows a Texas official came to the facility to remove child from Millcreek. The timing came less than a month after federal judge in Texas ordered that state to develop a plan to remove children from out-of-state facilities that were part of the ongoing U.S. Senate investigation. Other states like California and Oregon have made efforts in recent years to remove children from being shipped out of state.

Companies respond

10 Investigates left repeated messages trying to reach representatives from the four companies for comment.

Only UHS and Acadia responded with emailed statements that did not directly answer our questions about what the companies planned to do to address these issues.

A spokeswoman for UHS wrote:

“At Universal Health Services (UHS), we are committed to providing superior quality, compassionate and responsive healthcare for our patients. Our facilities provide quality care based on evidence-based therapies and treatments that result in successful, long-term recovery. Our facilities are highly regarded, trusted providers of behavioral health services in the communities we serve. In 2021, our Behavioral Health Division cared for over 700,000 individuals via inpatient, outpatient and telehealth offerings. Patients rated their overall care as 4.4 out of 5 in satisfaction surveys. Of those surveyed, 91% indicated they felt better following care at one of our facilities.

Due to our HIPAA obligations to protect patient privacy, we cannot offer comment on specific patients or their care.

Our staff are screened rigorously prior to hiring and undergo significant training on appropriate de-escalation techniques and safe patient interactions. While we strive for zero incidents, due to the thousands of employees at our facilities treating millions of patients, isolated and rare negative events do occur such as the ones you have highlighted. When such events happen and employees may fail to comply with facility policies, training and expectations, we investigate vigorously and take appropriate remedial and corrective actions up to and including termination of the employees involved. We also notify any law enforcement or regulatory agencies as required when such incidents occur and work collaboratively with those agencies investigating such matters.”

Acadia provided a lengthy statement that did not respond directly to 10 Investigates’ questions. Instead, a public relations firm offered this statement attributed to Acadia which read in part:

“Healthcare privacy regulations forbid us from discussing particular patient cases or incidents. However, it is very important to recognize that the facilities you mentioned have and continue to accept patients who could be in less than therapeutic environments such as juvenile detention, foster care, even facing homelessness had it not been for our facilities.

The fact is that our facilities accept these at-risk youth when truly no other facility will. In all instances involving Ohio youth, we cooperate closely with Ohio’s Office of Families and Children (SIC) (and with other state agencies as necessary). We take these cases because all children deserve hope and healing.

It is also highly relevant to point out that prior to 2020 – when Covid-19 took hold of everyone’s life – the acuity of our typical youth patient was within the psychiatric parameters for the at–risk population we serve. During the past two years, many of the cases we have received from Ohio (and other states) were exceedingly challenging due to the background and acuity of the patients by the time they were referred to us. In many instances, state agencies implored our facilities to take these patients, knowing the only other option was juvenile detention. Incidents rose in direct relation to the admission of these much higher-risk patients we were asked to accept.

Despite the challenges of the above population and circumstances, our facilities have worked to continuously improve our treatment programs and patient care, reduce the number of incidents, and given hope to hundreds of youths who previously had very little.

Regarding Detroit Behavioral Institute (“DBI”), we want to ensure you accurately frame the circumstances. The facility was administratively closed in mutual agreement with the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. In its 13-year history, DBI helped thousands of children and adolescents through serious mental health and substance use issues, providing a source of hope and healing for those in desperate need.

And as your research has no doubt uncovered, the behavioral health industry is very highly regulated. In fact, over the past 18 months Millcreek alone has experienced more than 200 events of auditors and case workers coming on campus touring our facilities and meeting with and interviewing patients. These audits and visits happen during business hours, overnight and on weekends. The outcomes of these visits and audits have repeatedly demonstrated that our operations at Millcreek are in compliance and the patients are well taken care of.

Given the population of high at-risk youth we serve, incidents do occur. The staff at our facilities are well-trained to de-escalate situations. The issues that led to the incident are then addressed immediately and all notifications made.

We are very proud of our staff and programs. And while your story will focus on a very small percentage of cases we serve, we want your viewers to know that the care and healing we provide these youth have saved countless lives and instilled a sense of hope when these kids needed it most.”

Agencies respond

Both ODJFS and FCCS declined to do on-camera interviews with 10 Investigates.

In emailed statements, both agencies said that do provide oversight and monitoring.

A spokesman for ODJFS wrote: “We provide oversight and monitoring in a number of ways, most notably through a child protection oversight and evaluation process that regularly examines local PCSA's delivery of child welfare services to children and families, including outcome indicators involving child safety, child permanency, and child and family well-being among other statutory responsibilities…”

A spokeswoman for FCCS wrote that the agency has reduced the number of out-of-state placements in recent years. Her response read in part:

“…when children are placed in residential settings we do monitor the facility to make sure that they have continued their license with the licensing body. As a matter of practice, our caseworkers are also required to visit youth at in-state or out-of-state facilities on a monthly basis. During those visits, staff inquiries (sic) about conditions within the facility and safety issues from the children in care. Obviously, we are also observant of physical surroundings when we visit. We also have a provider services department that prior to COVID, made yearly site visits to each institution where we had children placed and we are resuming those visits now.”

Do you have something you want 10 Investigates to look into, email us at 10investigates@10tv.com.