More than 1.9 million needles have been handed out to drug users in Columbus over the past two years as part of an effort to prevent the spread of diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C.

But a months-long investigation by 10 Investigates found there may be unintended problems with the needle access program – that discarded needles are popping across central Ohio.

What’s more – drug users tell 10 Investigates the free clean needles being distributed can also end up being sold on the black market.

While many drug users we interviewed praised the program for its benefits that include preventing them from having to share needles, some of those same drugs users admitted the relaxed nature of the Columbus program makes it prone to abuse.

Discarded needles

Of the more than 1.9 million needles distributed since 2016, roughly 114,000 used syringes have been returned (a figure the city’s health department just began counting in 2017).

There is no data for how many syringes were returned in 2016.

10 Investigates wanted to know – what’s happening to all the other needles?

“We believe they are being disposed of properly,” said Nancie Bechtel with Columbus Public Health, which oversees the needle access program.

But 10 Investigates found evidence that needles are being discarded all across central Ohio. We found them in alleyways, behind businesses, along railroad tracks and near schools and sidewalks in Columbus.

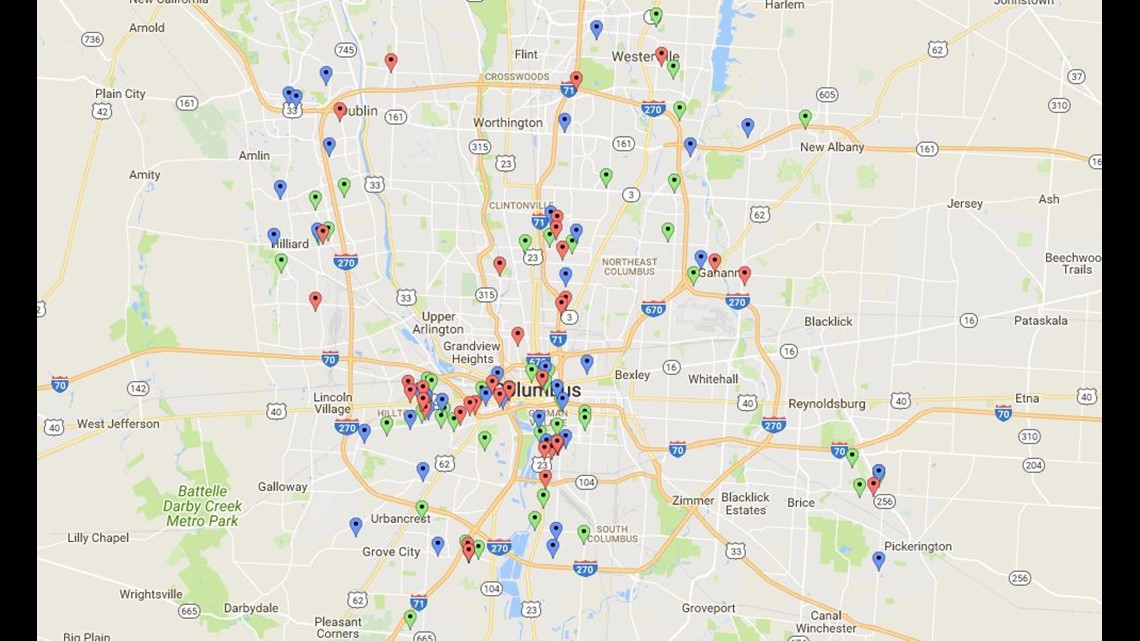

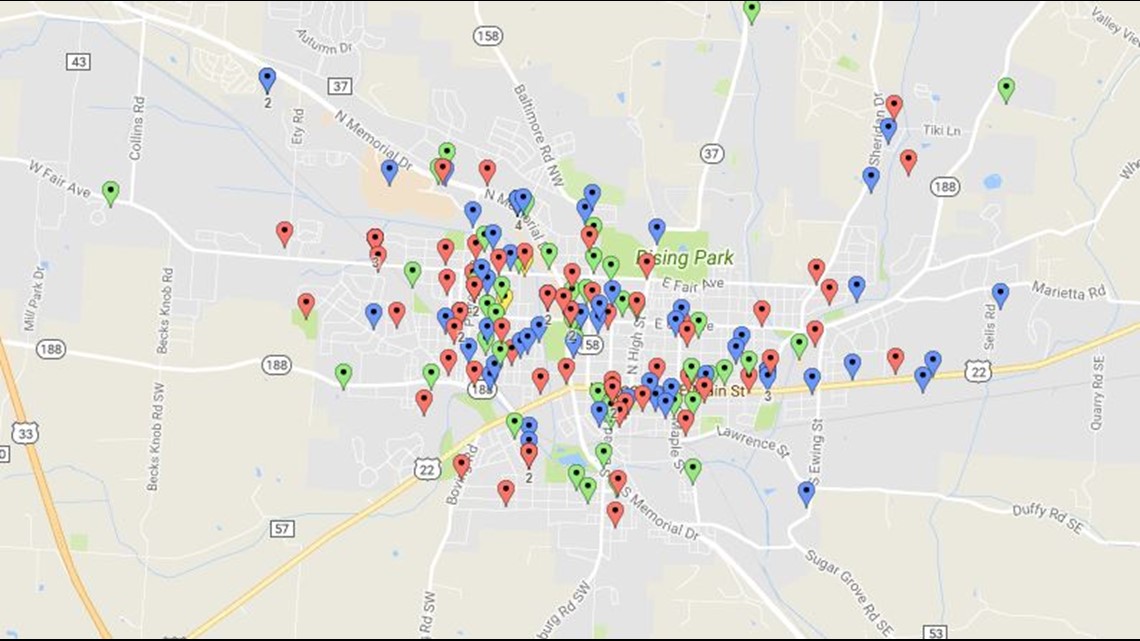

We then expanded our search to include citizen complaints to various police departments and city services centers in central Ohio. 10 Investigates compiled this map of citizen complaints that shows there have been 125 complaints about discarded needles just in the Columbus-area in 2017.

One city, Lancaster, had 173 complaints about discarded needles.

In a lengthy interview with 10 Investigates, Bechtel defended the effort saying that number of complaints did not outpace the number of needles being distributed.

But 10 Investigates found evidence of discarded needles that had not been reported to the city’s 311 center. And through several interviews with citizens, we found many of them stopped calling 311 – and instead opted on their own to dispose of the needles.

“We don't have reason not to believe that they're not being disposed of properly,” Bechtel said.

To be fair, 10 Investigates does not know where all the discarded needles came from, but we found evidence that some needles from the program appear to be among those being discarded improperly.

Many of the discarded needles we found were discovered near the same black plastic bags being distributed out to users enrolled in the needle access program. (See split side by side photo).

Peggy Anderson with Equitas Health, which runs the program at two locations in Columbus, also defended the relaxed nature of the program, saying the less restrictive philosophy is the best health policy.

"I don't know if they are ours, they could be. There could be others that are, you know, received from other areas or other ways. But I still don't believe that that's a negative from us in that our whole purpose is to keep people healthy or healthier – get them healthier,” Anderson said.

Citizens like John McCormack have taken matters into their own hands. McCormack has been cleaning up the area near his home on Morse Road near Blendon Township. On a recent October day, 10 Investigates followed McCormack as he picked up three discarded needles and threw them away.

“It's out of hand. And the city is not helping,” said McCormack.

When 10 Investigates asked him if he thought more effort should be put into picking up the discarded needles, McCormack said: “No, I think they should stop giving the needles out.”

When pressed further about how does the health department really know the needles are being disposed of properly, Bechtel said: “When clients come in, sometimes they are asked. But again, we continue with the education on every visit, they get sharps containers and they get materials (that show how to properly dispose of needles).

Bechtel and Peggy Anderson with Equitas Health say that they have distributed 9,000 sharps containers to the drug users and distributed fliers encouraging users to dispose of their used sharps in rigid plastic containers.

The city has also set up four drop-off bin locations to help with the proper disposal of the used needles, but it’s unclear how many needles have been dropped off.

Kelli Myers, a spokeswoman for Columbus Public Health, said the disposed needles are not counted but instead weighed. They have not received any weights from these drop off boxes.

Bechtel also says users are also encouraged to throw used needles away in the trash so long as they are placed in a sealed rigid plastic container like a bleach bottle or two-liter.

But other states like California and Oregon have banned that practice. When pressed on this, Bechtel said the World Health Organization encourages home disposal.

“And you can look that up,” she said.

We did.

While the WHO guidebook for those operating needle/syringe programs does mention that users can dispose of needles in rigid plastic containers, it does not specifically mention the trash.

Instead, the WHO guidebook suggests that needle access/exchange programs themselves should be responsible for the disposal.

The guidebook also states the used needles “can be a serious hazard for staff and the Needle Syringe program should consider itself responsible for all steps in the disposal process from collection of the used equipment from drug injectors until the equipment is ultimately destroyed.”

‘Needles are money’

Despite problems with needles being improperly discarded, some drug users say there are also concerns about people selling needles.

“The needles are money. And it's always going to be that way man because somebody is going to be getting high,” said Jeremy, a heroin user enrolled in the program. 10 Investigates has withheld his last name. “They sell them for $3 to $5 a needle.”

10 Investigates followed Jeremy’s journey for several weeks (You can watch some our raw interviews with him here).

When 10 Investigates pressed Jeremy if he had witnessed people selling the needles they received from the Columbus needle access program, he said: “I’ve bought them. I’ve went to the traps and had to buy them because I’ve run out. And they come from here. I mean, the exact same boxes. I’ve seen people here that take them there and sell them.”

A Columbus Police spokesman tells 10 Investigates that anecdotally narcotics officers have heard similar stories but they have not verified this and would not provide comment on specific narcotics investigations.

“If they are selling clean needles, somebody else is getting a clean needle,” Bechtel said during her interview with 10 Investigates. “We are giving people needles in good faith...to keep them from getting disease and to try to make a connection to get them in treatment. So if people are misusing the program, we're still going to operate the program in good faith.”

On one day, 10 Investigates watched a couple leave the needle access program and stop at a group of row houses in Franklinton.

The man opens his suitcase, shows its contents, and then goes inside.

Minutes later, we find him a few blocks away where he makes a hand-to-hand exchange with another man.

“If people are selling the needles then at least someone is getting a clean needle,” Bechtel said.

Columbus’ needle numbers

Unlike most needle exchanges that operate in Ohio, the needle access program in Columbus does not require drug users to provide their name or show identification.

There is also no requirement that users return their used syringes.

Users tell us they are provided with as many as 150 clean needles each visit.

"I think it's a great program they have going,” said Josh, a drug user who spoke to 10 Investigates in late September during a visit to the needle access program.

The program is offered three times a week at two separate locations run by Equitas Health. Organizers say it is largely funded through a mix of private donations, grant money and tax dollars.

Jeremy’s Journey

“You don’t get infections as often. You don’t get sicknesses. You don’t have to share needles with nobody,” said Jeremy, a drug user enrolled in the program. 10 Investigates has withheld his last name.

While Jeremy praised the program for providing him with clean needles every week, he was also critical of the relaxed nature he said has led to abuse.

When asked if he had witnessed people selling the needles from the needle access program, he said:

"I've bought them, yeah. I've went into the traps and had to buy them because I've run out. And they come from here. I mean, the exact same boxes. I've seen the people here that take them there and sell them,” he said.

Jeremy’s struggle with heroin spans more than a year and a half.

It’s cost him nearly everything.

“Everything. I mean my family, my house. All of it,” he said.

While he says the needle access program has helped him gain access to drug treatment, he says the treatment center doesn’t supply him with enough Suboxone to prevent himself from using heroin.

His habit, he says, began after he fell out of a tree at work. Like so many, he started off on pain medications and slowly switched to the cheaper option: heroin.

“So it's kind of an up and down thing. It's a battle. It's a bitch. I ain't gonna lie,” he said.

While the payoff may be years down the line, officials with the city’s health department and Equitas Health, which runs the needle access program, say the program is being operated on “good faith” as part of a larger effort to steer drug users towards treatment.

But little data is kept on how many users actually get there.

Federal privacy laws prevent the city’s health department from determining how many users complete the treatment program.

Volunteer quits

Lacey Dombroski said she volunteered at the needle access program for one day. But she said the sheer volume of needles, cookers and tourniquets being passed out was simply too much for her.

“It's a lot. It's just scary because you don't know where they end up if it's not mandated that they're exchanged.”

State data shows HEP C on the rise

Both Bechtel and Anderson acknowledge that it could be years before the city sees the payoff from the needle access program.

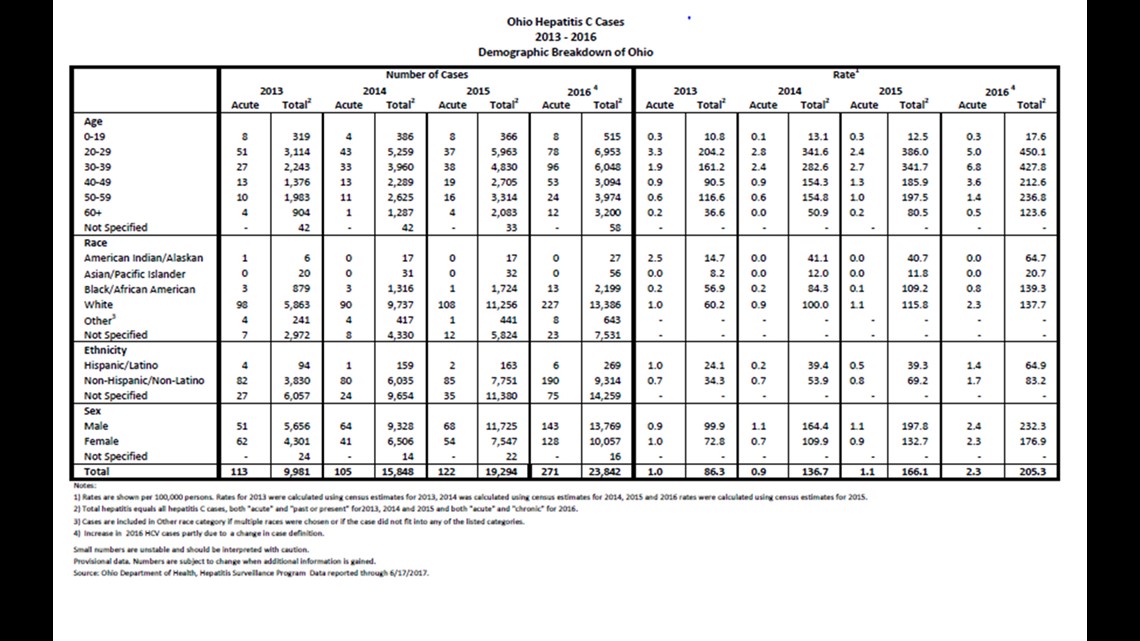

State health department data shows the number of Hepatitis C jumps from 9900 in 2013 to more than 23,000 cases in 2016.

The questions for some remain – are other unintended problems being left unchecked while the program with little oversight continues unabated?

And how does this help stop Ohio’s struggle with heroin?

“It’s just a never-ending circle,” Jeremy says. “Eventually you just either get enough of it like I did, or you just get stuck in the circle and you don't give a (expletive) and it ends up killing you.”