COLUMBUS, Ohio — Since 2015, 20 children have died while in the care and custody of Franklin County Children Services.

The agency that is tasked with removing children from harm acknowledges that 10 of the children died as a result of gun violence.

One child died from an overdose, another from a car crash, and congenital or prematurity health issues were to blame for several cases. The causes of a few deaths remain unclear, the agency said.

A four-part investigative series by 10 Investigates found these deaths were just some of the problems inside the foster care system.

Our reporting also uncovered other tragic events and found families who are still questioning what level of protection was actually provided by the foster care system.

When compared to the national average, the state of Ohio puts more kids into foster homes with strangers than kinship relatives. The state also lags behind the national average when it comes to reuniting families, according to a report from Child Trends.

As part of our reporting, 10 Investigates looked at court records, police runs to foster homes and Franklin County Children Services’ intake center, Medicaid reimbursement dollars given to behavioral treatment centers, and spoke with family members of the children who died.

We also spoke directly to the FCCS and other child services advocates who told 10 Investigates that their workload is becoming increasingly more challenging with additional referrals from juvenile court and children needing behavioral or mental health treatment.

In a 30-minute interview with Lara LaRoche, the intake director at Franklin County Children Services, chief investigative reporter Bennett Haeberle asked her directly:

When kids end up dead or taking another life, what role does the county play for that?

LaRoche said: “We play a role. Our community plays a role, right? Children are a product of our community. And we are all responsible for the health and wellness of all families in our community.”

But for those like Toni Howard, whose grandson died while in the custody of Franklin County Children Services in 2020, she questions what the agency did to protect him.

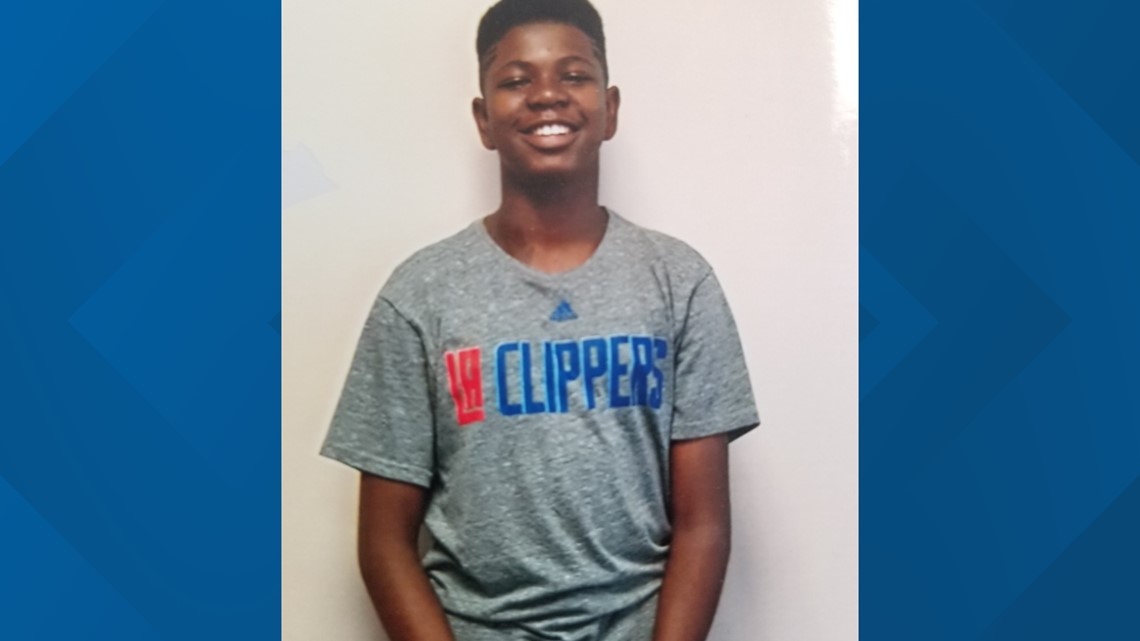

Her grandson, Dawaun Lewis-Taylor, died in late September of 2020. He was fatally shot on the north side of Columbus.

Toni and her husband, Lit, helped raise Dawaun after his mother died a few years ago from a suspected overdose. After her death, Toni said she noticed a change in Dawaun’s behavior. A domestic incident at home landed him in juvenile court.

Toni told 10 Investigates she was initially unaware that FCCS took custody of him and placed him at Maryhaven – a facility that no longer provides in-patient behavioral treatment for teens.

After a two-week stay there, Dawaun ran away after being assaulted at the facility by another teen, Toni said. In the months after his death, Maryhaven stopped its behavioral in-patient program for youths, something it said had been in the works prior to Dawaun’s death.

“After he was murdered, I contacted (FCCS). They immediately came out, dropped off his belongings said they could not assist with funeral expenses and then I get a letter saying the case was closed,” Howard said. “[Children] services did not go out looking for him. They came to our house and told us they do not have time to look for missing children. If Dawaun calls tell him to turn himself in, or you can turn him in.”

FCCS disputes this, telling 10 Investigates it does look for missing children.

In late October of 2020, almost a month after Dawaun’s death, Toni Howard showed 10 Investigates a letter she received from FCCS telling her “your case is closed.”

The letter went on to state: “although there is no longer any need for protective services to be provided by this agency, the following services are recommended: to please reach out to me if you need anything else in the future. Again, I am so sorry for your loss.”

Toni told 10 Investigates: “And for that clause to say ‘no need for protective services’ what were they protecting? They weren’t protecting him.”

Dawaun was killed six months before Ma’Khia Bryant. They are among the most recent deaths tied to those in the custody of the agency.

Last spring, Ma’Khia’s death drew national attention in part because she was fatally shot by a Columbus police officer on the same day as a jury returned a verdict against Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd.

Earlier this year, a Franklin County grand jury declined to indict Columbus police officer Nick Reardon – finding there was no probable cause to believe a crime occurred.

Body camera video shows him responding to the scene to find a fight involving several people. The video shows Ma’Khia Bryant wielding a knife and appearing to lunge near a woman as she is shot four times by the officer.

Ma’Khia had been removed from her mother’s home years earlier after a complaint was filed with FCCS raising concerns about Ma’Khia and her siblings, her mother Paula Bryant acknowledged during a recent interview.

But Paula Bryant says she is committed to reuniting her family and raises questions about the decisions made by the agency.

“The system failed my daughter, the system failed other children. And there needs to be some reform to the system,” Paula Bryant said.

A 10 Investigates’ review of police records to the foster home on Legion Lane where Ma’Khia was staying revealed at least 29 police runs – more than half of which were for missing persons reports. Others were for issues including assaults and fights.

Less than a month before her death, Ma’Khia’s sister called police to say that she had gotten in a fight and didn’t want to be in the foster home anymore.

10 Investigates asked FCCS’s intake director Lara LaRoche about this:

When placing kids in foster homes with active police runs, people without a knowledge of social work are going to look at that and say "this doesn’t seem right." So why does that happen?

LaRoche said: “Well, let me give examples that add context. Why would police respond to a foster home?”

She went on to explain that foster homes and facilities are required to call police if a child runs away.

“Youth are coming into our care, experiencing those behaviors, is it reasonable to believe that those behaviors will cease through the act of giving the agency custody? No,” LaRoche said.

Howard said her family is left feeling frustrated.

“It’s sad,” she said. “So who is held accountable? Or do they label them as a number or a problem child or ‘oh well.’ That’s a life that you took ownership of… So what happens?”

When asked what FCCS would say to the families of those who have died while in their care, LaRoche said: “We grieve with you…”

Caught in the Cycle series