Ohio's child behavioral health system is at a 'breaking point'

The number of children seeking help for depression, anxiety, and suicide is overwhelming the system because there are not enough therapists to treat them.

Waiting six months to a year for a child to see a mental health professional for ADHD, anxiety, depression or suicidal thoughts in Ohio is “unacceptable for sure,” says the Director of Ohio’s Mental Health and Addiction Services Lori Criss.

Mental health professionals across Ohio and across the country say their profession is at a "breaking point."

The number of children seeking help for depression, anxiety, and suicide is overwhelming the system because there are not enough therapists to treat them. That’s despite the fact that over the past three years Ohio has dedicated more than $1.2 billion for student wellness.

A new federal law mandates that, as of July 16, every state must have a call system for people to seek immediate help for mental health or substance use crises.

The 988 system is a dedicated call-in line for dispatching trained staff to respond to mental health and substance use emergencies. Ohio is working to get the new phone line up and running.

“It's a crisis consultation over the phone then links to other services and supports,” said Lori Criss, the director of Ohio Mental Health and Addiction Services.

Lisa Denino of Columbus has seen firsthand what it is like to be placed on hold as she struggled to find a mental health therapist for her daughter.

Her daughter was adopted from Russia and at 3 years old she says her daughter began expressing behaviors that she knew immediately were not normal.

“Around three she started to display really behaviors that were not typical. They weren't the terrible twos or anything that other moms I spoke to were familiar with,” she said.

Denino says she desperately tried to find help for her daughter.

“Nobody wanted to work with a toddler and insurance wasn't going to cover it anyway and nobody believed me until they saw the video,” she said.

She showed us the video of her daughter on the floor screaming.

Denino says it took her three years on a waiting list to find a child therapist to work with her daughter.

The waiting, she says, just made her child worse.

“It gets progressively worse because as she is supposed to be maturing and fitting into societal norms that child is not doing that so there are more and more disappointments every day,” she said.

Ohio's Child Behavioral Workforce

According to this white paper, written by the Ohio Council on Behavioral Health and Family Service Providers, the lack of therapists in Ohio has created “a perfect storm that jeopardizes behavioral health care providers' ability to respond.” The report raised serious concerns about the rates of child suicide in Ohio.

“In Ohio, there was a 27.4% increase in the number of suicide deaths between 2010 and 2019. Suicide was the second leading cause of death among Ohioans between the ages of 10 and 34 years and the 11th leading cause of death overall.”

Those statistics mirror what is happening across the country.

“Suicide is the eighth leading cause of death among youth aged 5 to 11 in the United States, and suicide rates in this age group increased nearly 15% annually between 2012 and 2017,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, research on suicide deaths among this age range has been limited.

“Results showed that suicide in children is most often associated with mental health concerns, prior suicidal behavior, trauma — including abuse or neglect, exposure to domestic violence, suicide or the death of a family member — or peer, school or family-related problems.”

Child psychotherapist Kristen Santel runs one of the few child therapy offices in the city. She says her office is constantly getting requests from parents looking for help.

Landers: Even if you could double your staff could you still meet the demand?

Santel: No. we could not meet the demand if we tripled our staff.

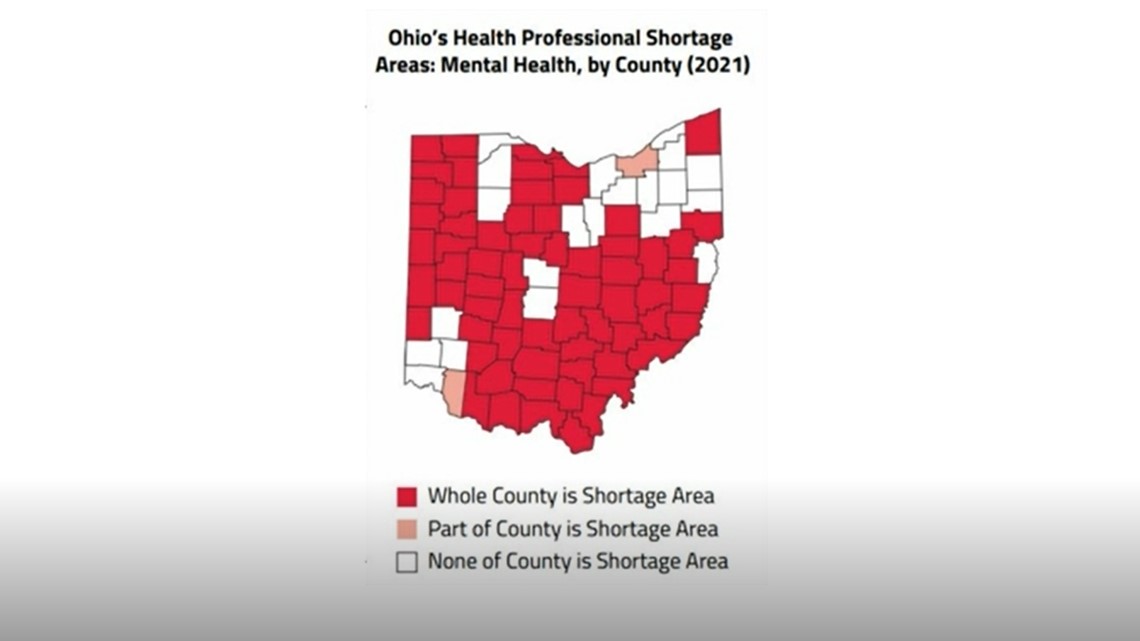

More than 75% of the counties in Ohio have what's called mental health HPSA’s or Health Professional Shortage Areas. These are areas where no child health counselor exists.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Ohio has 116 HPSA’s meeting just 38% of the need. The state would need 111 health care providers to meet the demand.

“It’s truly at a breaking point in terms of the sheer numbers of people who cannot get access to care,” says Jared Skilings of the American Psychological Association. “The waitlists for mental health clinicians across the whole country are absolutely out of control."

Denino agrees.

She says it wasn't until she had to call the police, because she couldn't control her daughter, that she says she was able to move up on the waiting list at Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

Landers: So what does that tell you?

Denino: Was my child going to have a police record before any therapist would talk to her? That's insane.

Below are some red flags that parents can look out for:

Where's The Help

Director Criss says the state is working on a plan to help retain and grow the workforce in the field of child mental health.

“The proposal we put together with the department of Medicaid calls for 200 million dollars that comes from the federal government. That is one-time funding that we believe can be invested in growing this workforce,” Criss said.

A spokesperson for Governor Mike DeWine said, “When he took office, less than 40% of childcare providers receiving public funding were quality rated. Within 20 months, all publicly funded providers were rated. That means each provider had to meet a set of standards to provide for the academic success, as well as the health and well-being, of our kids. Governor DeWine has also expanded the Infant & Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation Program to provide a pipeline of workers specially trained to address the unique mental health needs of Ohio’s youngest residents. Over the biennium, we have provided $15.7 million to expand this certification program and have funded the certification of 121 full-time counselors/consultants and 7 master trainers.”

The state says early childhood intervention to catch mental health illnesses in children is working based on screening tests that show:

- 38% of students were screened for depression

- 34% substance abuse

- 28% trauma

- 41% suicide screening

In March 2020, Nationwide Children's Hospital opened the Big Lots Behavioral Health Pavilion, making it the largest behavioral treatment and research center in the United States. Fast forward two years later, the head of the department says the unit has expanded from 44 beds to 56 beds and it can't find enough workers to add more.

“If we had more staff we would open more beds,” says Dr. David Axelson, Chief of the Department of Psychiatry and Medical Director of the Big Lots Behavioral Pavilion at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. “Some of our programs the waits are several months some of the not so as long."

Even children who express suicidal thoughts must wait.

“Some of the prioritized kids will get in in three or four days,” said Dr. Axelson.

He says the problem with child behavioral health started long before the pandemic. The pandemic just exasperated it.

“Depression and anxiety have increased significantly in our kids,” said Dr. Axeslon.

But without more people to care for those kids, he says, he's worried about what will happen.

He says Ohio lacks child psychiatrists.

“We are probably four times lower than what we truly need,” said Dr. Axelson.

Inside Kirsten Santel’s practice in Columbus, which specializes in child therapy, therapists say wait times are longer than they've ever been.

“If someone were to email today it would probably be a year before I could see their kid, says Danielle Weatherholtz who is one of the few people in Columbus that works with children as young as 3 years old.

Before the pandemic, most of the therapists in the practice say wait times were a few months.

“We get requests for services seven to 10 times a day for new clients that we just can't support,” Santel said.

Turning parents away, they say, has always been an issue.

Now, it's happening more often because of the demand.

Michelle Jordan-Frias, a social worker and child therapist, said it's heartbreaking to tell a parent no.

Landers: What is it like for you to tell a parent no?

“Wait times are the longest they've ever been in my practice," he said.

Like many professional therapists in central Ohio thought Children's Hospital's Behavioral Center would help absorb more kids in need.

Landers: So, it didn't provide the relief you were hoping?

Weatherholtz: No, and I hear that from families all the time, but they just got this new building I just hear they increased all these services and I called them and it said 6 months to a year.

Insurance Companies and Low Reimbursements

The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act was enacted in 2008 and requires insurance coverage for mental health conditions, including substance use disorders, to be no more restrictive than insurance coverage for other medical conditions. But few in the industry including the U.S. Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy believe the law is being carried out as intended.

“Despite in 2008 passing the mental health parity law and patient equity act which was supposed to bring reimbursement for mental health care services parity with other traditional health care services that is not being adequately enforced,” he said.

If long wait times and a lack of child therapists weren't bad enough, there’s another problem.

Those who work in child therapy say insurance companies like Medicare haven't raised their reimbursement levels to keep up with inflation.

“Insurance reimbursement through Medicaid is maybe half of what I would make if people were private paying,” says Jordan-Frias.

“We just never end up getting paid for things no matter how many times we spend on the phone no matter how many times we resubmit claims,” Santel said.

As a result, more therapists are dropping insurance coverage and only accepting those who can pay out of pocket. Others are leaving the industry which further limits the number of children who need help. The result,

“People will get sicker and mental health will get worse,” Santel said.

As for Lisa Denino, she says she feels lucky she found a therapist that's helping her daughter. She just wishes there were more of them.

“Basically, they are saints on earth. We just don't have that many saints,” she says.

Getting Help: Resources for parents and children

The Ohio Department of Insurance is hosting free, live webinars in February to help consumers and healthcare professionals understand mental health and substance use disorder insurance benefits, director Judith L. French announced.

During the webinars, mental health insurance experts will explain how the department regulates mental health and substance use disorder insurance benefits, help consumers and healthcare professionals determine the benefits in a health plan and provide a tutorial about the mental health and substance use disorder insurance benefits tools and resources on the department's website, including how to file a complaint and appeal a denied claim.

The webinars are:

- Consumer Tips for Understanding Mental Health Insurance Benefits, Feb. 15, 11:30 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. Register here

- Understanding Mental Health Insurance Benefits for Healthcare Professionals, Feb. 24, noon - 1 p.m. Register here

Additional resources

- Ohio CareLine: 1.800.720.9616 | More info here.

- Ohio Crisis Text Line: Text Keyword 4HOPE to 741 741 | More info here.

- SAMHSA’s National Online Treatment Finder

- County ADAMH Board Directory: Ohio’s 50 county Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services (ADAMHS) Boards serve as the local planning authorities for community behavioral health services. They contract with local community mental health and substance use disorder prevention, treatment, recovery support and harm reduction service providers to help ensure access to a full continuum of behavioral health services across the lifespan. The Boards receive allocations from OhioMHAS, federal funding and, in many areas, local levy dollars.

- Franklin County ADAMHS serves Greater Columbus and all of Franklin County.

- Mental Health and Recovery Board for Licking-Knox Counties: 740-522-1234

- Delaware-Morrow Mental Health and Recovery Services Board: 740-368-1740

- Mental Health and Recovery Board of Clark, Greene and Madison Counties: 937-322-0648

- Paint Valley ADAMH Board (Fayette, Highland, Pickaway, Pike and Ross Counties): 740-773-2283

- Fairfield County ADAMH Board: 740-654-0829

- Nationwide Children’s Hospital and Franklin County Youth Psychiatric Crisis Line: 614-722-1800. A skilled professional is available 24/7 for families and can support/triage them to the appropriate level of care.

If you can not find help right away, you can contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at the number below. Crisis counselors are standing by 24 hours a day, seven days a week.