COLUMBUS, Ohio — In 66 of Ohio’s 88 counties, fewer than 1 in 2 residents have received at least one dose of vaccination against COVID-19, which has killed more than 661,000 Americans since the pandemic began.

The low vaccination coverage, found via an analysis of state data from Sunday, indicates vast swaths of the state remain vulnerable to a surging, hyper-transmissible variant of the virus that causes the disease.

The vaccines are free to recipients and have been widely available to the public since late March, suggesting much of the population remains unvaccinated by choice.

Despite a crescendo from hospitals and health officials warning of increasingly scarce bed capacity and pandemic-fatigued staff, Ohio counties’ low vaccination rates underscore the frustration of some public health workers as chunks of their community abstain from safe and effective vaccines.

“I’m not really sure we’re going to change some people’s minds about vaccines,” said Pamela Riggs, commissioner of the Sidney-Shelby County Health Department, in the third-least vaccinated county in the state.

“I don’t know what else to say. It has just been a very frustrating experience.”

Last week, several children’s hospitals issued a bleak warning of increasing rates of children seeking intensive care due to COVID-19. In southern Ohio, only four ICU beds were available on Friday among general hospitals in the region, according to the Ohio Hospital Association.

The Southern Ohio Medical Center, a hospital in Portsmouth, warned in a social media post Saturday that its ICU was at capacity and is being “stretched to the breaking point,” raising a possibility that a crash or gunshot victim may not have a hospital bed there when needed.

"What we are experiencing is very real," wrote the CEOs of nine hospitals or hospital networks in southern Ohio and West Virginia in a letter Monday pleading for community buy-in on masks and vaccination.

"It isn't a political issue; it's a medical issue. When we look at our patient data, a vast majority of hospitalized COVID patients have not received the COVID vaccine"

Sherri Kovach, president of the Central Ohio Trauma System, said in an interview last week that besides a swelling roll of COVID-19 hospitalizations, the 36 counties she oversees are reporting an uptick in people seeking care they put off last year. Rising case rates in unvaccinated areas are predictable, she said.

“Our communities showing the lowest vaccine rates are the ones being hit the hardest,” she said. "We just need to continue to educate until people hear. That’s the way out of this.”

On a state level, 53% of Ohioans (64% of adults) have received at least one dose of vaccination against COVID-19. This trails the national rate of 63% of vaccine-started Americans (75% of American adults).

However, unvaccinated people are not randomly distributed through the state; using statewide data can mask substantial vulnerability to outbreaks in certain, less-vaccinated counties.

On the low end is Holmes County — where many residents are Amish and tend to abstain from vaccination — where just 17% of the population is vaccinated.

According to state data as of Sunday, another 33 counties, generally smaller and rural, have vaccination rates between 31% and 40%.

Some of them like Lawrence (33%), Vinton (35%) and Meigs (38%) don’t have hospitals in the county, further raising the stakes for residents who develop COVID-19 and need urgent care.

Delaware County is the only one in Ohio to surpass the national rate — 67% of the population there has started their vaccine process. Other urban and suburban counties trail Delaware including Lake (60%), Cuyahoga (58%) and Medina (58%).

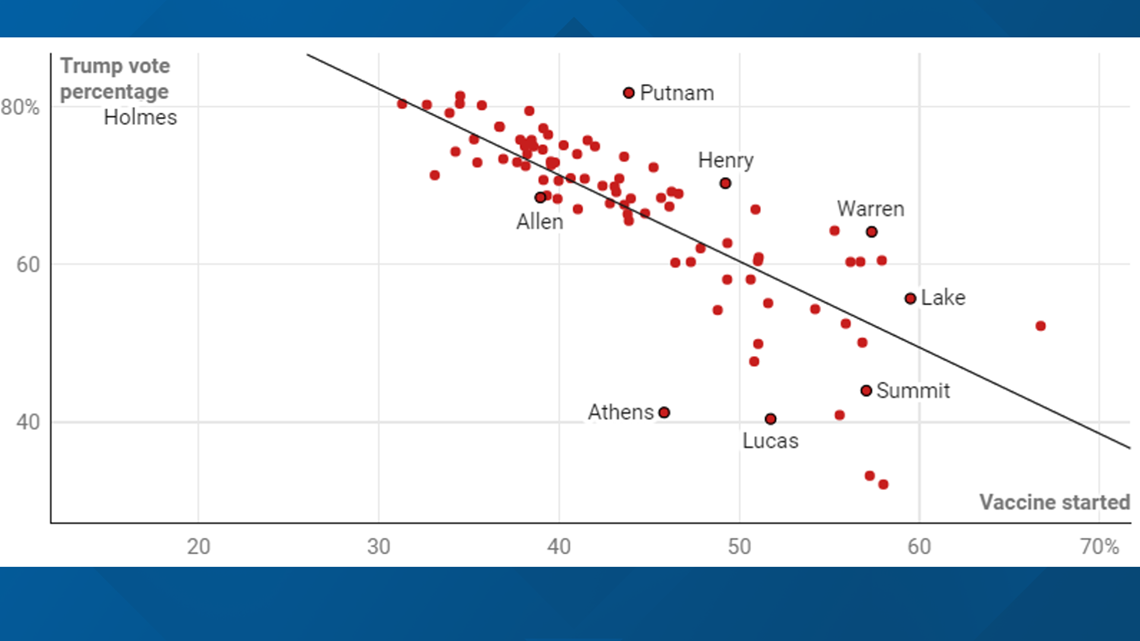

Alongside population level and urban/rural splits in vaccination rate, the health data coupled with 2020 electoral results reveals another pattern; the higher the rate of residents who voted for President Donald Trump, the less vaccinated the county.

“A lot of this was politicized early on, and this is not a political issue, this is a health care crisis,” Kovach said.

COVID-19 vaccine uptake vs. 2020 Presidential Election

Last week, President Joe Biden announced a new federal strategy to combat COVID-19. It’s built around requiring large employers to either require vaccinations from employees or test unvaccinated employees on a weekly basis.

Several Republican governors quickly announced plans to mount a lawsuit to stop the mandate.

Gov. Mike DeWine took something of a middle ground, calling Biden’s plan a “mistake” but avoiding any clear answer on whether he’d join the lawsuit. On Monday, he said to reporters he spoke to Attorney General Dave Yost about the lawsuit but provided no further detail. Bethany McCorkle, a Yost spokeswoman, did not respond when asked if Yost is planning to sign on to a lawsuit. She said Biden knows he is "acting unlawfully" and Yost is reviewing the order and relevant law.

Dan Tierney, a DeWine spokesman, said Monday that things like vaccine mandates “that distract from the vaccination conversation are not particularly helpful.” He said they inject politics into the equation, which complicates any effort of persuasion.

When asked about the low vaccine uptake in most Ohio counties, he emphasized outreach and education as the route to higher vaccine coverage. He pushed back against analyzing vaccine coverage against the Trump vote.

“In some ways, this is urban versus rural,” he said. “Throughout this process, we’ve had to respond to questions of, when you do orders of a statewide nature, why would a bar closure apply to an urban club the same way as a rural dive bar?”

With more than 3,400 Ohioans currently hospitalized for what is now a vaccine-preventable disease, there’s little evidence of a common cause in the body public to stave off the virus. About 53% of Ohio students, many of them too young to legally receive a vaccine, attend a school with a mask mandate, according to Tierney. Conservatives who dominate the General Assembly called for lawsuits to stop Biden’s mandate. Some are pushing legislation to broadly weaken Ohio’s vaccination laws.

The conflict has escalated to the point of Tuscarawas County's health commissioner writing an open letter last month detailing an online harassment campaign and pictures of her four-month-old infant circulating on the internet.

At the Central Ohio Trauma Center, Kovach said hospital workers are exhausted.

“A staff can only work 70, 80 hours a week for so long,” she said. “They are burned out. They’ve been doing that since last year, running not only their hospitals and ERs, but COVID testing, COVID vaccines. They are burned out.”

Riggs, at Sidney-Shelby Health Department, said she’s trying to keep morale up with the occasional pizza or donuts for employees. She tells them not to take it personally when people won’t get vaccinated, or when schools ignore their mask recommendations (which they did).

“You’re almost sometimes afraid to speak out loudly because you become somewhat of a target,” Riggs said.