COLUMBUS, Ohio — When Barb Cordle died, she had $6.18 to her name.

“That’s exactly how she wanted it,” her son, Randy Cordle, said. “She was probably upset that she hadn’t given away the $6.”

Although Barb didn’t have much, she gave everything she could. She was a devout Catholic who searched for God’s purpose for her life. She found that purpose one day in 1985 when she visited a homeless shelter and met a man with AIDS.

“No one would go near him,” Randy said. “She went over, hugged him, picked up his stuff and moved him into the house."

That man was Barb’s first patient at Pater Noster House – a hospice for people with HIV and AIDS. Within days, two more patients showed up at Pater Noster, illustrating the need for HIV and AIDS care in Columbus.

Many of Barb’s patients were part of the LGBTQ+ community and couldn’t access care in the city’s hospitals.

“Pater Noster provided 24/7 medical care, food, a place to stay and also fellowship and friendship in a dignified place for a lot of folks to spend their last days,” Ohio History Connection’s Svetlana Harlan said.

Barb opened Pater Noster House during a time of intense homophobia, made even worse by the AIDS epidemic. Pater Noster became an important resource for the LGBTQ+ community. People who were terminally ill were able to die with dignity, while others got stabilized with medication and went on to live full lives.

“Their identity was being validated, and they were not made to feel ostracized by society,” Harlan said.

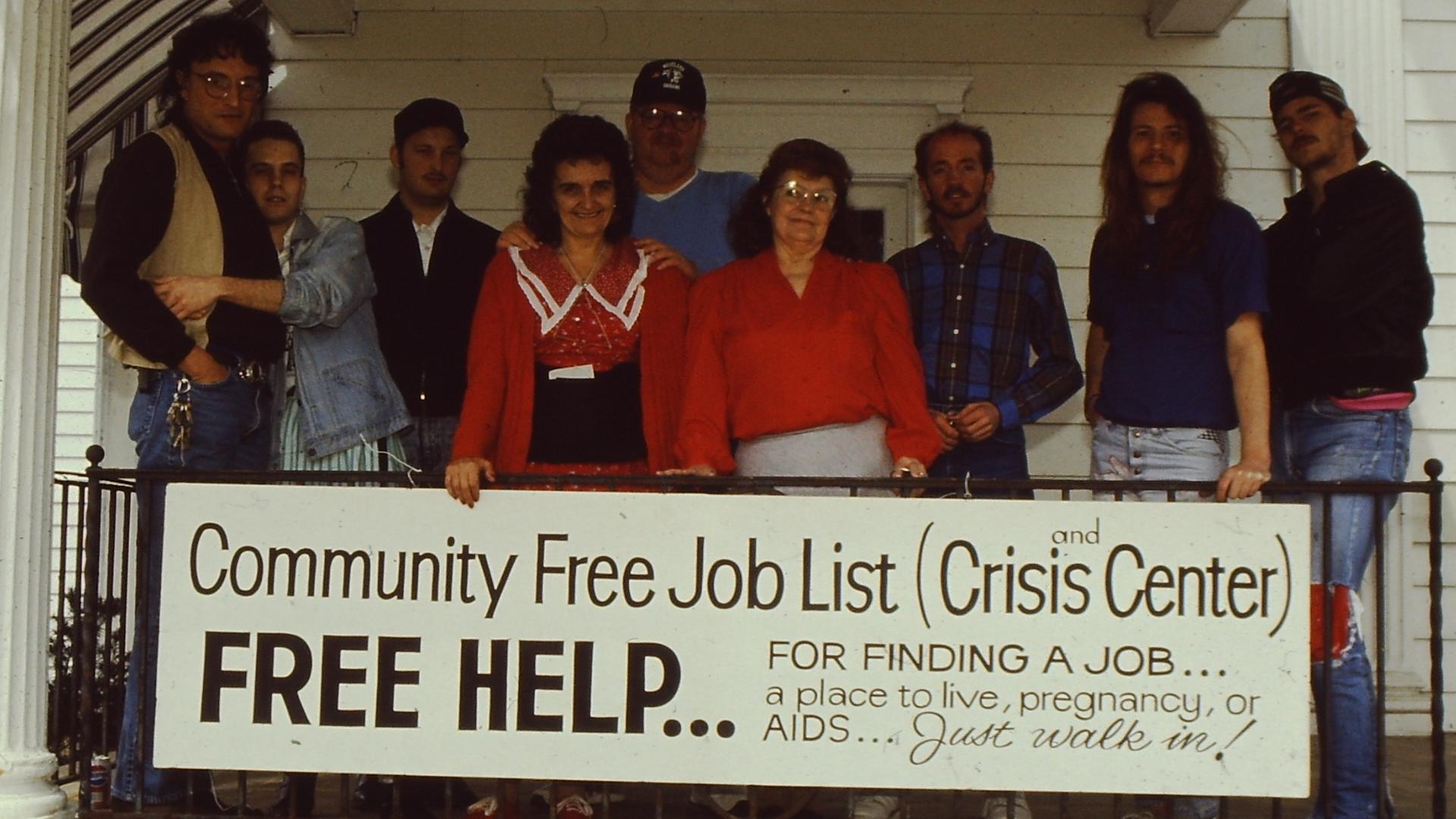

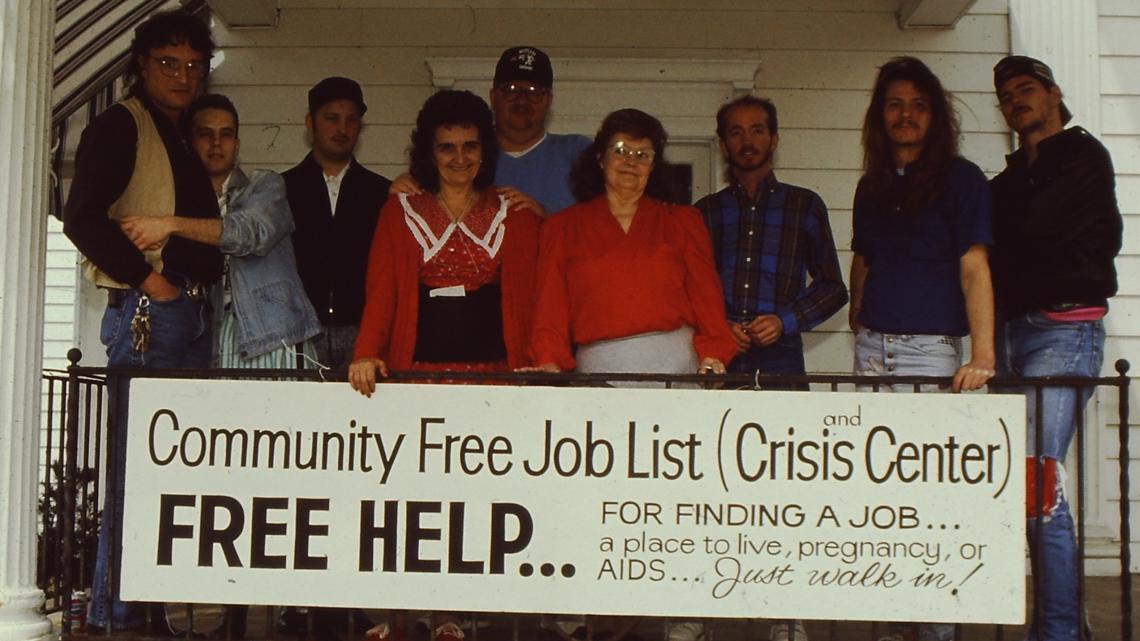

Barb and volunteers cared for more than 900 people between 1985 and 2000. Many of the volunteers cared for the dying as they fought their own HIV infections.

“They worked alongside those who were dying, knowing they’d be in that same bed someday,” Randy said.

A patient named David Kirby was famously photographed by Therese Frare at Pater Noster in 1990. The picture showed his body ravaged by aids and his father cradling him. It defied the stereotype that people with the virus died in isolation.

Kirby's photographer was published by Life Magazine and used in a Benetton ad. It's been credited with humanizing the AIDS epidemic.

"We were seeing these images of a typical American family who was surrounding their loved one who was dying of this disease," Harlan said. "It showed that in fact people were there for their loved ones."

Pater Noster closed 24 years ago but remains an important part of Ohio’s history. That’s why the Ohio History Connection plans to honor it with a historical marker.

It's one of 10 planned markers across the state to honor significant LGBTQ+ sites. There are currently 1,700 historical markers in Ohio, but only three honor LGBTQ+ history.

“They did it literally out of love for humanity and for people,” Randy said.